| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Original Article

Volume 6, Number 2-3, September 2017, pages 44-48

The Glanzmann’s Thrombasthenia in Tunisia: A Cohort Study

Hejer Elmahmoudia, b, d, Meriem Achoura, c, Nejla Belhedia, Hend Ben Nejia, Kaouther Zahraa, c, Balkis Meddeba, Emna Gouidera, c

aUR14ES11, Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia

bNational Center for Nuclear Science and Technology, Sidi Thabet, Tunis, Tunisia

cHemophilia Treatment Center, Aziza Othmana Hospital, Tunis, Tunisia

dCorresponding Author: Hejer Elmahmoudi, UR14ES11, Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia

Manuscript submitted June 1, 2017, accepted July 10, 2017

Short title: Glanzmann’s Thrombasthenia

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh330e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (GT) is a rare autosomal-recessive bleeding disorder with uncommon neonatal revelation. It is due to abnormalities of quantitative and/or qualitative αIIbβ3 integrin. This cell adhesion receptor is essential for platelet aggregation and allows the formation of a hemostatic plug if the vessel is damaged by injury. The clinical picture of GT is variable, with mucocutaneous bleeding due to non-functional platelets. Management requires a good expertise in bleeding disorders. We describe the clinical and the epidemiological data of GT in Aziza Othmana Hospital Hemophilia Center.

Methods: This was a retrospective study of all patients with GT monitored and treated in our hemophilia center during the period of 2011 - 2015.

Results: Twenty-seven patients among the 35 patients included in our hemophilia center registry were studied. The most common sign encountered is the gingival bleeding. In our women cohort, one completed her pregnancy. The consanguinity is present with a frequency of 62%. Treatments used depending on the case are tranexamic acid, platelet transfusion, packed red blood cells and rFVIIa, respectively.

Conclusion: GT is relatively frequent in Tunisia and especially in the North of the country which can be explained by the high consanguinity in our population.

Keywords: Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia; Tunisia; Bleeding disorders; Consanguinity; Flow cytometry; Platelet aggregation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (GT) is an autosomal-recessive bleeding platelet disorder characterized by a defective platelet integrin αIIbβ3 receptor [1]. Prevalence of GT is unknown but it is estimated to be about 1.1 million and it is encountered in populations with a high rate of consanguinity [2]. A slight female predominance (58% vs. 42%) is reported, similar to other inherited platelet disorders (IPDs) [3]. Mucocutaneous bleeding starting in childhood is the major clinical finding and includes epistaxis, gingival bleedings, and easy bruising. Bleeding severity is quite variable. Three types of GT are described: patients with severe αIIbβ3 deficiency (expression levels < 5%), moderate αIIbβ3 deficiency (10-20% expression) and with higher expression (> 20%) but with a dysfunctional αIIbβ3. They are respectively classified as having type I GT, type II GT and the variant form of GT [4]. Patients with GT do not need therapy on a regular basis, but will always require treatment during surgical procedures, controlling bleeding after injury, and during spontaneous bleeding episodes. The current standard of treatment of bleeding episodes in patients with GT is the use of local measures alone or in conjunction with anti-fibrinolytic therapy first, followed by platelet transfusion. rFVIIa is restricted to patients with failure to control bleeding after platelet transfusion, due to immunization [5].

Among 80 patients with GT reported in Tunisia (annual global survey WFH, 2014) [6], our Hemophilia Center in Aziza Othmana Hospital (AOHHC) follows 35 patients who represent 43.75% of all reported patients.

The aim of this study was to describe the demographic, clinical and biological features of GT patients recruited in AOHHC.

| Methods | ▴Top |

The AOHHC follows patients with bleeding disorders living in the North of Tunisia. In this context, our study is interested in patients with GT diagnosed in our hemophilia center or sent to us for management. Data were extracted from the hemophilia center registry [7]. For each patient, we raised demographic and clinic information such as age, sex, geographical origin, bleeding history, type of bleeding events, presence of similar family living or deceased cases and a potential consanguinity.

Testing was carried out using peripheral blood samples stored in tubes containing EDTA as an anticoagulant for the platelet numeration and platelet glycoprotein expression with flow cytometry. Peripheral blood samples were stored in tubes containing sodium citrate for platelet function. The platelet function exploration was carried out using platelet aggregation to different agonists (ristocetin, epinephrine, adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and collagen). Peripheral blood smear was performed directly at fingertips in order to appreciate morphology and presence or absence of platelet clumps.

| Results | ▴Top |

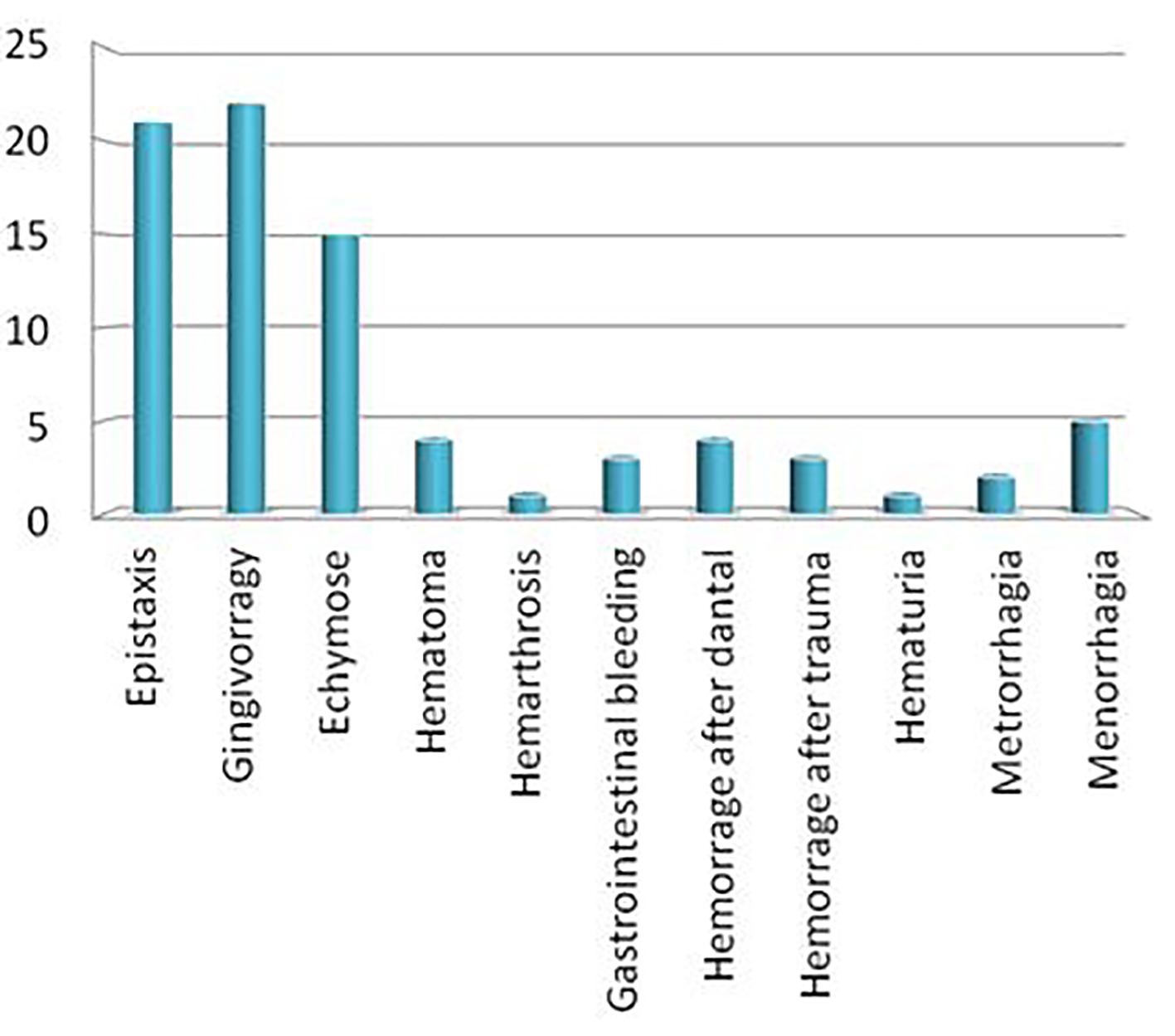

Our cohort comprises a total of 35 patients with GT belonging to 32 families. Data for analysis were available only for 27 patients. The age at the diagnosis is ranging from 0 to 4 years, with a median of 18 months. The median actual age is 22 years. The sex ratio is 0.928 (13/14). For Tunisian patients whose origin is known (11/27), the majority of them are from the North of Tunisia (7/11). The consanguinity was observed in 17 cases and 10 patients were sporadic cases. Thirteen patients had a family history of a bleeding disorder. All patients are still alive except one who died at the age of 31 years. The easy bruising is the major cause of the diagnosis circumstances in our cohort. The diagnosis was done using platelet aggregation, flow cytometry or both of them, respectively in 29%, 55% and 18%, respectively. The clinical data of our cohort are very heterogeneous as follows: gingival bleeding (81%), epistaxis (77%), easy bruising (55%), hematoma 14%, gastrointestinal bleeding 11%, post-dental extraction bleeding 14%, hematuria 3% and hemarthrosis 3%. Our cohort comprises 14 women, 10 of whom reached the age of puberty. Five women (35%) developed menorrhagia and two (14%) developed metrorrhagia. One woman completed her pregnancy to term with a successful delivery and two women presented problems of sterility. One woman benefited from Higham score and she was under hormonal treatment in order to prevent bleeding (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Clinical data of patients with GT followed in AOHHC. |

Biological data showed a normal platelet count, with absence of platelet clumps in the blood smear. Platelet function analyzer (PFA) is prolonged in three patients tested for this assay. The light transmission aggregometry (LTA) showed an impaired aggregation using all physiological agonists (adrenaline, ADP, collagen and arachidonic acid). Among the 15 patients who beneficiated of flow cytometry, nine had a total deficiency of αIIbβ3 (< 5% of αIIbβ3 expression), two had a moderate deficiency and four had a normal level of αIIbβ3 for whom the diagnosis was confirmed with aggregometry.

Tranexamic acid was used for 54% of our patients, and platelet transfusion was used for 13 patients. Only four patients were treated with rFVIIa and three for intensive gastrointestinal bleeding not controlled. The fourth patient developed platelet inhibitors with no efficacy of platelet transfusion. Hormonal therapy was used for four women with menorrhagia. For 17 patients, we needed packed red blood cells (PRBCs).

| Discussion and conclusion | ▴Top |

In the last data (2011) concerning bleeding disorders in our hemophilia center, we reported 23 patients with GT [7]; between 2011 and 2015, we identified 12 novel cases. Despite of the rarity of this pathology, the statistics revealed that GT is less rare in our country. Like an autosomal rare bleeding disorder, the GT is common in ethnic groups that exhibit higher incidence of consanguinity, such us Palestinian, Jordanian, Iraqi Jews, and South of India [8]. In our cohort, 68% of the cases are from consanguineous marriages which explain higher incidence of this pathology in our center and in second time in our country. Consanguinity was reported in 82% of cases in the South [9]. According to the annual global survey 2014, Tunisia reported 80 cases with GT and our center followed 35 of them (43.75%). In other studies concerning autosomal bleeding disorders (FVII deficiency, FV + FVIII deficiency and FXIII deficiency), we also reported higher incidence in our country resulting from the consanguineous marriage [10-12]. These data give us specificity for bleeding disorders. When we compare our data with countries that have a population number near to the Tunisian population or with countries from the North of Africa having the same situation, we found that only one patient and 19 patients are reported respectively from Portugal and Belgium with population numbers of 10,813,837 and 10,449,361, respectively, while we reported as mentioned above 35 patients in our hemophilia center and 80 cases in Tunisia with a population number of 10,937,521 according to the hemophilia global survey 2014 [6]. We can explain the data with the high consanguineous marriage in our country. Comparing to countries with high consanguinity such us our neighbor, Algeria in the North of Africa, we also have higher prevalence for GT since we had 1.81 times patients more than Algeria while it has 3.5 times population more than Tunisia. Comparing Algeria to Belgium, we found that the incidence of GT in Algeria is lower, which may be explained by the presence of non-identified or underdiagnosed patients, so the necessity of establishing a patient register is very useful [13, 14]. On the other side, the high prevalence in Belgium can be explained by the foreign origin of elevated number of Belgians [6]. Concerning GT data from Morocco, it seems that it has also a relatively higher prevalence, the most cases are from the North of country and the consanguinity was reported in 54.5% of cases [15]. When we explore Egyptian data for GT, 439 cases were reported in a population of 86,895,099 which means that the prevalence of GT in Egypt seems to be less frequent than Tunisia while it has 7.9 times more in population [6] (Table 1). This difference in prevalence of GT between our country and the other two North African countries mentioned above can be explained by our screening strategies concerning bleeding disorders such us GT, especially if we compare our current results with the lasted published in 2012 concerning our AOHHC [7], or mentioned in the hemophilia global survey 2011 (Table 2). In this context, we must mention that the presence of a patient register is a valuable tool which enabled us to collect all necessary data concerning patients and to identify the novel cases.

Click to view | Table 1. Demographic Data According to Global Survey 2014 and Tunisian Census 2014 |

Click to view | Table 2. Comparison Between Demographic and GT Data in Tunisia and in Our AOHHC |

According to the global survey 2014, 80 patients were reported from Tunisia (data collected from three centers), 43.75% of them are followed in our hemophilia center which means that GT is most frequent in the North of Tunisia, since 25/27 patients live in the North of Tunisia and only two patients are from Gafsa (South of Tunisia) (Fig. 2). Since 50% of the Tunisian population lives in the North, we have almost 50% of the patients in our center.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Repartition of GT patients according to their residence. The majority of patients (21) with GT followed in AOHHC are from the North of Tunisia. Only two of the patients are from the South of Tunisia. |

Some studies revealed sex ratio of about 1 which is verified in our cohort with 14 women against 13 men (51% versus 49%) [2].

All patients were diagnosed at childhood, in age ≤ 4 years. As reported it is the corresponding period of clinical expression of GT [5].

Clinically, the most common sign encountered in our cohort is gingival bleeding followed by epistaxis and easy bruising respectively which are also the most reported in the literature. The hematoma is one of the rare signs described in patients with GT but we reported four patients (14%) suffering from them and in one patient the hematoma is post-traumatic. Hemarthrosis is reported in the literature [16], but was not observed in our cohort. Only two patients suffered from bleeding after circumcision while it is a frequent sign described in other cohorts [17]. The same observation is carried out, concerning dental extraction bleeding in only four patients (14%). Concerning bleeding in women, we can conclude that menorrhagia has a low frequency (35%), since it occurs only in five women in our cohort, compared to the described frequency in GT [18]. One woman achieved her pregnancy with natural delivery under platelets, while it is rare in a thrombasthenic patient since it often results in important hemorrhage requiring sometimes blood transfusions and threatening the vital prognosis of the mother [19]. For the diagnosis of GT, we use in our laboratory more than one specific test such us LTA which is extremely specific for GT, since platelet fails to aggregate with any agonist [20]. We use also flow cytometry in order to identify a platelet receptor dysfunction and/or deficiency using specific monoclonal antibodies. In the case of GT, CD41 and CD61 levels are much reduced or absent against normal levels of CD42 [21]. In our protocol patient care and since the use of antifibrinolytic is coming available, the use of platelet transfusions or rFVIIa is limited. In the case of active bleeding episode, the first treatment used is tranexamic acid and if necessary we used platelet transfusion. rFVIIa is used only in four situations where the above modalities fail to control bleeding episodes [22].

We demonstrate that GT is relatively frequent in our country. This is due to the high consanguinity in our population. GT is a disease, requiring a rigorous and multidisciplinary care because hemorrhagic syndromes can be severe and fatal. That’s why the analysis of the clinico-epidemiological data is a useful tool for monitoring and improving their quality of care. In order to offer for our patients a genetic counseling, our future perspective is to identify the molecular defect for this pathology with a probability of a founder effect since the majority of our patients belong to the North and the North East of Tunisia (Fig. 2) and this can be explained with the derive effect.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the medical and nursing stuff of the HTCAOH and the homeostasis laboratory of Aziza Othmana Hospital. We would like to thank our patients for their help and cooperation.

Author Contributions

HE performed the research analyzed the data and wrote the paper; MA and NB analyzed the data; FB, WE and KZ contributed in the data collection; BM and GE designed the research.

Grant Support

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Palla R, Peyvandi F, Shapiro AD. Rare bleeding disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 2015;125(13):2052-2061.

doi pubmed - Nurden AT, Nurden P. Inherited disorders of platelet function: selected updates. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(Suppl 1):S2-9.

doi pubmed - Sandrock-Lang K, Wentzell R, Santoso S, Zieger B. Inherited platelet disorders. Hamostaseologie. 2016;36(3):178-186.

doi pubmed - Nurden AT, Nurden P. Congenital platelet disorders and understanding of platelet function. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(2):165-178.

doi pubmed - Solh T, Botsford A, Solh M. Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and current and emerging treatment options. J Blood Med. 2015;6:219-227.

doi pubmed - World Federation of Hemophilia Report on the Annual Global Survey 2014. World Federation of Hemophilia: 2015. 1425 Rene Levesque Boulevard West, Montreal, Quebec.

- Elmahmoudi H, Chalbi A, Ben-Lakhal F, Borji W, Zahra K, Zorgan M, Meddeb B, et al. Regional registry of bleeding disorders in Tunisia. Haemophilia. 2012;18(6):e400-403.

doi pubmed - Haghighi A, Borhany M, Ghazi A, Edwards N, Tabaksert A, Haghighi A, Fatima N, et al. Glanzmann thrombasthenia in Pakistan: molecular analysis and identification of novel mutations. Clin Genet. 2016;89(2):187-192.

doi pubmed - Ben Aribia N, Mseddi S, Elloumi M, Kallel C, Kastally R, Souissi T. [Genetic profile of Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia in south Tunisia. Report of 17 cases (11 families)]. Tunis Med. 2005;83(4):208-212.

pubmed - Elmahmoudi H, Ben-Lakhal F, Elborji W, Jlizi A, Zahra K, Sassi R, Zorgan M, et al. Identification of genetic defects underlying FVII deficiency in 10 patients belonging to eight unrelated families of the North provinces from Tunisia. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:92.

doi pubmed - Elmahmoudi H, Wigren E, Laatiri A, Jlizi A, Elgaaied A, Gouider E, Lindqvist Y. Analysis of newly detected mutations in the MCFD2 gene giving rise to combined deficiency of coagulation factors V and VIII. Haemophilia. 2011;17(5):e923-927.

doi - El Mahmoudi H, Amor MB, Gouider E, Horchani R, Hafsia R, Fadhlaoui K, Meddeb B, et al. Small insertion (c.869insC) within F13A gene is dominant in Tunisian patients with inherited FXIII deficiency due to ancient founder effect. Haemophilia. 2009;15(5):1176-1179.

doi pubmed - Keipert C, Hilger A. Response to Italian registries on bleeding disorders. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(3):273.

doi pubmed - Dolan G, Makris M, Bolton-Maggs PH, Rowell JA. Enhancing haemophilia care through registries. Haemophilia. 2014;20(Suppl 4):121-129.

doi pubmed - Mukendi JL, Benkirane S, Masrar A. [Glanzmann thrombasthenia: about 11 cases]. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:268.

doi pubmed - Urakawa H, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, Katsumi A, Ishiguro N. Glanzmann thrombasthenia detected because of knee hemarthrosis: a case report. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19(6):521-523.

doi pubmed - Mokhtar GM, Tantawy AA, Adly AA, Telbany MA, El Arab SE, Ismail M. A longitudinal prospective study of bleeding diathesis in Egyptian pediatric patients: single-center experience. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23(5):411-418.

doi pubmed - Caki Kilic S, Sarper N, Zengin E, Aylan Gelen S. Screening bleeding disorders in adolescents and young women with menorrhagia. Turk J Haematol. 2013;30(2):168-176.

doi pubmed - Siddiq S, Clark A, Mumford A. A systematic review of the management and outcomes of pregnancy in Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Haemophilia. 2011;17(5):e858-869.

doi - Albanyan A, Al-Musa A, AlNounou R, Al Zahrani H, Nasr R, AlJefri A, Saleh M, et al. Diagnosis of Glanzmann thrombasthenia by whole blood impedance analyzer (MEA) vs. light transmission aggregometry. Int J Lab Hematol. 2015;37(4):503-508.

doi pubmed - De Cuyper IM, Meinders M, van de Vijver E, de Korte D, Porcelijn L, de Haas M, Eble JA, et al. A novel flow cytometry-based platelet aggregation assay. Blood. 2013;121(10):e70-80.

doi pubmed - Poon MC, Di Minno G, d’Oiron R, Zotz R. New insights into the treatment of glanzmann thrombasthenia. Transfus Med Rev. 2016;30(2):92-99.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.