| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 5, Number 2, June 2016, pages 70-73

Pulmonary Thromboembolism Associated With Mixed-Type Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

Mingfeng Leea, Takakazu Higuchib, c, Ryosuke Koyamadab, Sadamu Okadab

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

bDivision of Hematology, St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

cCorresponding Author: Takakazu Higuchi, St. Luke’s International Hospital, 1-9, Akashi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8560, Japan

Manuscript accepted for publication April 11, 2016

Short title: VTE Associated With Mixed-Type AIHA

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jh263w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A 56-year-old woman presented with mixed-type autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) and was complicated with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE). While DVT/PTE has been recently recognized as a complication of AIHA, there has been no reported case of mixed-type AIHA complicated with DVT/PTE. Mixed-type AIHA is a rare subtype of AIHA and both warm- and cold-type autoantibodies were assumed to have contributed to the development of VTE/PTE in the present case. As severe AIHA and PTE share common symptoms, it is important to consider a possibility of the complication of PTE in the management of AIHA patients.

Keywords: Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; Mixed-type; Deep vein thrombosis; Pulmonary thromboembolism; Complements

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a rare autoimmune disorder in which autoantibodies against red blood cell (RBC) surface antigens are produced, resulting in premature peripheral destruction of RBCs, with estimated incidence in adults being 1 - 3 per 100,000 person-years [1, 2].

The majority of AIHA have either warm-type AIHA, cold agglutinin disease (CAD), or paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria (PCH); however, some AIHA patients simultaneously develop both warm- and cold-type autoantibodies and are referred to as mixed-type AIHA [3-5]. On the other hand, while it is still not widely recognized that AIHA is a risk factor of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), 10-25% of AIHA patients are reported to be complicated with thromboembolism and a considerable number of AIHA patients complicated with DVT/PTE are unrecognized and, thus, not treated [6-10]. Moreover, to our knowledge, complication of thromboembolism in patients with mixed-type AIHA has not been reported before and the contribution of each anti-RBC autoantibody subtype to the development of thromboembolism is unknown.

We herein report a case of mixed-type AIHA complicated with DVT/PTE at presentation of AIHA.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 56-year-old Japanese woman was admitted for the evaluation and treatment of severe anemia. She had been suffering from progressive weakness, dizziness, and dyspnea which had started 2 weeks before. She visited another hospital and severe anemia with jaundice was noted. The hemoglobin (Hb) level was 2.8 g/dL, the total bilirubin (T-Bil) was 6.0 mg/dL, and the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 963 U/L. Packed RBCs were transfused and, on the next day, she was transferred to our hospital. She had no past medical history except depression for which she had been taking fluvoxamine, mianserin and etizolam for 8 years. She had quitted smoking 3 years before. She had a daughter and had no family member who had any kind of hematological or autoimmune diseases.

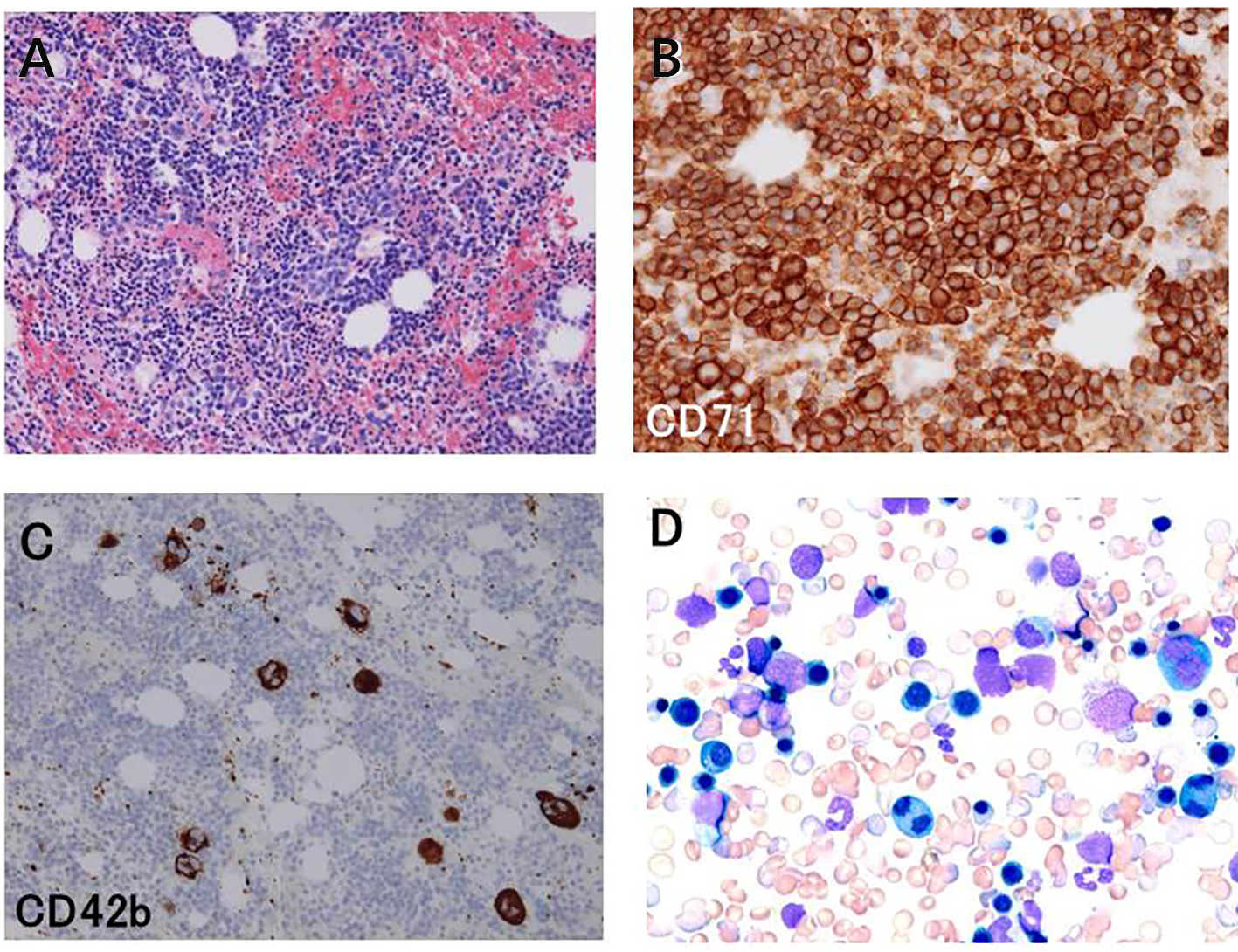

On transfer, she was pallor and the conjunctivae were icteric. The liver and the spleen were not palpable. Neither subcutaneous nor mucosal hemorrhage was noted. The laboratory data showed that the white cell blood count was 6.3 × 109/L, the RBC count was 1.38 × 1012/L with 13.14% reticulocytes, the Hb level was 6.1 g/dL, the hematocrit was 15.1%, and the platelet count was 82 × 109/L. The coagulation tests revealed that the D-dimer was elevated to 62.7 μg/dL. The blood chemistry showed that the T-Bil was 6.0 mg/dL, the aspartate aminotransferase was 42 U/L, the alanine aminotransferase was 16 U/L, and the LDH was 974 U/L. The haptoglobin level was below the level of detection. The direct and indirect Coombs’ tests were both positive and monospecific antibodies revealed that the RBCs were coated with immunoglobulin (Ig) G and fragments of the third component of complement (C3). The IgG level was 914 mg/dL, IgA was 280 mg/dL, IgM was 89 mg/dL, C3 was 43 mg/dL (reference range, 65 - 135) and the fourth component of complement (C4) was 2 mg/dL (reference range, 13 - 35). The platelet-associated (PA) IgG was 73.2 ng/107 cells (reference range, 5.0 - 25.0). The antinuclear antibody was positive with a ratio of 1:80 with homogenous pattern. Other autoantibodies studied, including anti-double stranded DNA, anti-smith, anti-SS-A, anti-cardiolipin, and anti-cardiolipin-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant were all negative. The cold agglutinin titer was 1:256. The hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C virus, anti-human immunodeficiency virus, and anti-adult T-cell leukemia virus antibodies, and anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG were negative. The bone marrow examination showed marked erythroid hyperplasia with increased megakaryocytes (Fig. 1). Warm-type AIHA possibly with immune thrombocytopenia was diagnosed and oral prednisolone (PSL) was started at 1 mg/kg/day with RBC transfusion to maintain the Hb level above 7.0 g/dL.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Examination of clot section specimen (A, B, and C) and wedge smear cytology (D) of the bone marrow aspirate. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (A) showed hypercellular bone marrow (× 100). Immunostaining with antibodies against CD71 (B) and CD42b (C) revealed that the eythroid cells were markedly increased and the megakaryocytes were also increased (× 200). Immature and binucleated erythroid cells were frequently observed (D, × 200). |

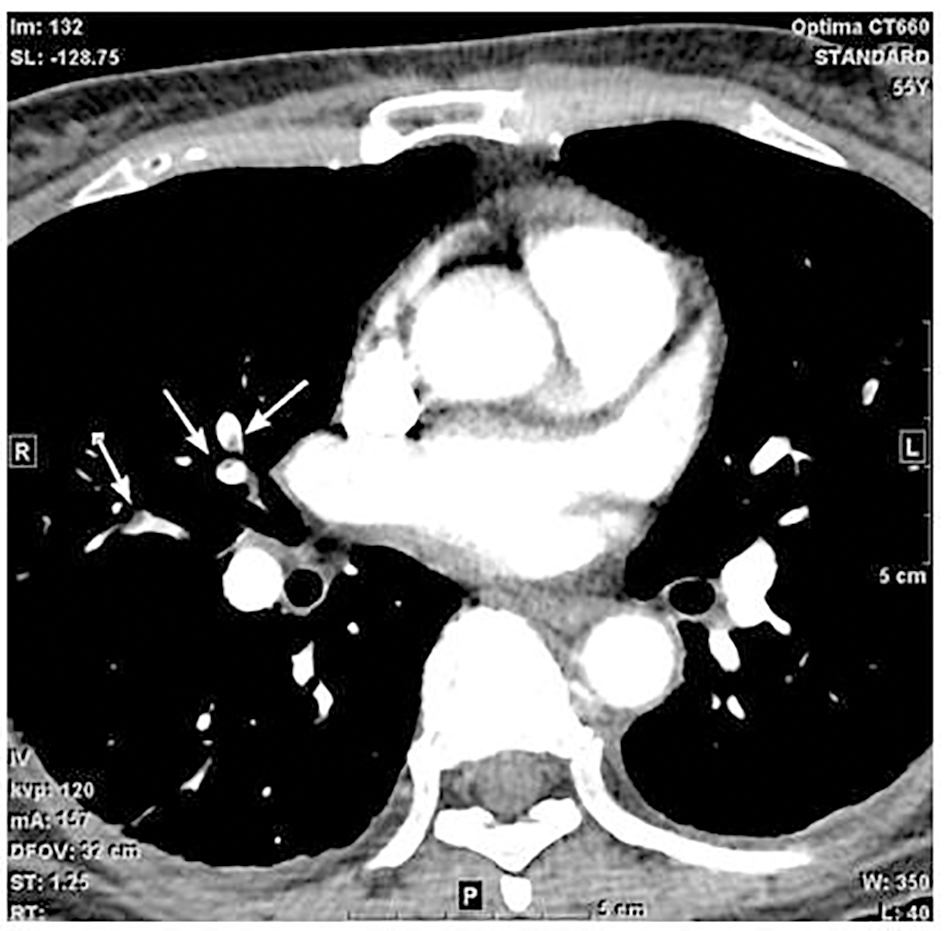

Although she did not have chest symptoms, the elevated D-dimer level and dyspnea suggested PTE and contrast-enhanced computed tomography was performed, which showed multiple filling defects in the bilateral pulmonary arteries diagnostic of multiple acute PTE (Fig. 2). In addition, DVT of the right popliteal vein was detected. The anticoagulation therapy with heparin was started.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed multiple filling defects in the bilateral pulmonary arteries (arrows). These findings are diagnostic of multiple acute pulmonary thromboembolism. |

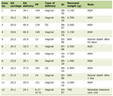

The thermal amplitude of the cold agglutinin was studied by incubating O type RBCs and the serum of the patient, which was serially diluted in normal saline, at room temperature, 4, 30, and 37 °C (Table 1). The patient’s serum contained cold agglutinins which were active at 30 °C and judged to have wide thermal amplitude and the patient was diagnosed as mixed-type AIHA.

Click to view | Table 1. Thermal Amplitude of the Cold Agglutinin |

The anemia responded to PSL and the platelet count also increased to 180 × 109/L. The Hb level was maintained at between 9 and 10 g/dL with a tapered dose of PSL and remained thereafter with low complement levels. With resolution of thrombi, heparin was switched to warfarin and she was discharged.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The majority of AIHA cases have either warm-type AIHA, CAD, or PCH based on the characteristics of the causative autoantibody and warm-type AIHA comprises about 75% of all AIHA cases. On the other hand, approximately 6-8% of AIHA patients simultaneously develop both warm-type antibody and cold agglutinin and are referred to as mixed-type AIHA [3-5], although the frequency is reported to be lower when more strict diagnostic criterion is applied [11].

While it is still not widely recognized, DVT/PTE is a rather common complication of AIHA [6-10, 12-16]. The association between DVT/PTE and AIHA has long been recognized since 1967, when Allgood and Chaplin reported that PE was complicated in five of their cohort of 47 patients and was the most common cause of death [17]. More recently, a cross-sectional [13] and three cohort studies [12, 14, 15] reported that the risk of complicating DVT/PTE was increased in AIHA patients and a meta-analysis of these studies demonstrated that the pooled risk ratio of DVT/PTE was 2.63 [16]. While case series of AIHA showed that 10-25% of AIHA patients were complicated with thromboembolism and a substantial number of them had anti-phospholipid antibodies (APLA) [6-10], about 15% of AIHA patients who had thromboembolism did not have APLA, suggesting that AIHA itself is associated with thromboembolism [6, 10]. Various mechanisms have been proposed for the hypercoagulability in AIHA patients. Disruption and loss of RBC membrane expose negatively-charged membrane phosphatidylserine on the surface which provides a surface for formation of the tenase and prothrombinase complex [6]. Antibody-mediated decrease in cytoskeleton protein may also contribute to this process. Cytokine-induced expression of tissue factor on monocytes and endothelium may also be involved [6]. In addition, microparticles released from RBC fragments during hemolysis are thought to trigger the coagulation cascade [18]. Moreover, sequestration of nitric oxide by free plasma Hb released from damaged RBCs can lead to uninhibited platelet aggregation and vascular smooth muscle dystonia, resulting in clot formation [19]. Notably, as the present case had mixed-type AIHA, the contribution of cold agglutinin to the development of thromboembolism should be considered. Destruction of RBCs in patients with warm-type AIHA is primarily extravascular sequestration by phagocytosis in the spleen and intravascular hemolysis is unusual [20]. In the case of CAD, although the major mechanism of hemolysis is extravascular hemolysis by the reticuloendothelial cells in the liver [21, 22], intravascular hemolysis mediated by terminal complement complex may occur in up to 10% of the patients [23]. Profound anemia and low complement levels seen in the present case suggested that intravascular hemolysis due to the activation of terminal complement complex was operative, releasing excess free Hb into the blood stream, thus contributing to the development of thromboembolism. Presently, the patient is still mildly anemic with low complement levels, which suggests continuous activation of complement system and low grade hemolysis, without any signs of the recurrence of thromboembolism; however, as she is still on anti-coagulation therapy with warfarin. the contribution of cold agglutinin to the development of thromboembolism remains speculative until more cases are studied.

The patient had mild thrombocytopenia and increased megakaryocytes in the bone marrow with elevated PAIgG level and the platelet count subsequently elevated with the start of PSL. These findings suggested a possibility of immune thrombocytopenia and it appeared likely that she had Evans’ syndrome. Immune thrombocytopenia has also been reported to be a risk factor of DVT [13, 14]. However, as the consumption of platelet by thrombus formation may have contributed to the decrease in the platelet count, the diagnosis remained unconfirmed.

In conclusion, the present case shows that it is important to consider a possibility of DVT/PTE when treating patients with AIHA because the clinical presentation of severe AIHA may resemble that of PTE, which can be fatal and require immediate optimal intervention.

| References | ▴Top |

- Chaplin H, Avioli LV. Grand rounds: autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137(3):346-351.

doi pubmed - Sokol RJ, Hewitt S, Stamps BK. Autoimmune haemolysis: an 18-year study of 865 cases referred to a regional transfusion centre. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282(6281):2023-2027.

doi - Shulman IA, Branch DR, Nelson JM, Thompson JC, Saxena S, Petz LD. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia with both cold and warm autoantibodies. JAMA. 1985;253(12):1746-1748.

doi pubmed - Sokol RJ, Hewitt S, Stamps BK. Autoimmune hemolysis: mixed warm and cold antibody type. Acta Haematol. 1983;69(4):266-274.

doi pubmed - Kajii E, Miura Y, Ikemoto S. Characterization of autoantibodies in mixed-type autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Vox Sang. 1991;60(1):45-52.

doi pubmed - Pullarkat V, Ngo M, Iqbal S, Espina B, Liebman HA. Detection of lupus anticoagulant identifies patients with autoimmune haemolytic anaemia at increased risk for venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol. 2002;118(4):1166-1169.

doi pubmed - Hendrick AM. Auto-immune haemolytic anaemia - a high-risk disorder for thromboembolism? Hematology. 2003;8(1):53-56.

doi pubmed - Roumier M, Loustau V, Guillaud C, Languille L, Mahevas M, Khellaf M, Limal N, et al. Characteristics and outcome of warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults: New insights based on a single-center experience with 60 patients. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(9):E150-155.

doi pubmed - Barcellini W, Fattizzo B, Zaninoni A, Radice T, Nichele I, Di Bona E, Lunghi M, et al. Clinical heterogeneity and predictors of outcome in primary autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a GIMEMA study of 308 patients. Blood. 2014;124(19):2930-2936.

doi pubmed - Lecouffe-Desprets M, Neel A, Graveleau J, Leux C, Perrin F, Visomblain B, Artifoni M, et al. Venous thromboembolism related to warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a case-control study. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(11):1023-1028.

doi pubmed - Mayer B, Yurek S, Kiesewetter H, Salama A. Mixed-type autoimmune hemolytic anemia: differential diagnosis and a critical review of reported cases. Transfusion. 2008;48(10):2229-2234.

doi pubmed - Ramagopalan SV, Wotton CJ, Handel AE, Yeates D, Goldacre MJ. Risk of venous thromboembolism in people admitted to hospital with selected immune-mediated diseases: record-linkage study. BMC Med. 2011;9:1.

doi pubmed - Yusuf HR, Hooper WC, Beckman MG, Zhang QC, Tsai J, Ortel TL. Risk of venous thromboembolism among hospitalizations of adults with selected autoimmune diseases. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2014;38(3):306-313.

doi pubmed - Yusuf HR, Hooper WC, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Boulet SL, Ortel TL. Risk of venous thromboembolism occurrence among adults with selected autoimmune diseases: a study among a U.S. cohort of commercial insurance enrollees. Thromb Res. 2015;135(1):50-57.

doi pubmed - Zoller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with autoimmune disorders: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. Lancet. 2012;379(9812):244-249.

doi - Ungprasert P, Tanratana P, Srivali N. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2015;136(5):1013-1017.

doi pubmed - Allgood JW, Chaplin H, Jr. Idiopathic acquired autoimmune hemolytic anemia. A review of forty-seven cases treated from 1955 through 1965. Am J Med. 1967;43(2):254-273.

doi - Horne MK, 3rd, Cullinane AM, Merryman PK, Hoddeson EK. The effect of red blood cells on thrombin generation. Br J Haematol. 2006;133(4):403-408.

doi pubmed - Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P, Gladwin MT. The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin: a novel mechanism of human disease. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1653-1662.

doi pubmed - Packman CH. Hemolytic anemia due to warm autoantibodies. Blood Rev. 2008;22(1):17-31.

doi pubmed - Berentsen S, Tjonnfjord GE. Diagnosis and treatment of cold agglutinin mediated autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood Rev. 2012;26(3):107-115.

doi pubmed - Swiecicki PL, Hegerova LT, Gertz MA. Cold agglutinin disease. Blood. 2013;122(7):1114-1121.

doi pubmed - Brodsky RA. Complement in hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2015;126(22):2459-2465.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.