| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 3, September 2015, pages 196-201

Plasmablastic Lymphoma in the Testis and Duodenum: A Case Report and Literature Review

Jennifer Y. Shenga, d, Daniel A. Baika, Lilly Yib, Nasheed Hossainc, David Essexc

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Temple University Hospital, 3401 North Broad St, Philadelphia, PA, USA

bTemple University School of Medicine, 3401 North Broad St, Philadelphia, PA, USA

cDepartment of Hematology and Oncology, Temple University Hospital, 3401 North Broad St, Philadelphia, PA, USA

dCorresponding Author: Jennifer Y. Sheng, Department of Internal Medicine, Temple University Hospital, 3401 North Broad St, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication July 13, 2015

Short title: PBL in Testis and Duodenum

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jh217w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare and highly aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). There are over 300 reported cases of PBL, of which over 120 are reported in HIV-positive patients. Of HIV-negative patients, patients were either immunocompetent or immunosuppressed transplant recipients. Initial reports highlighted cases arising in the oral cavity of HIV patients and this remains the most prevalent site of disease. However, other sites such as the gastrointestinal tract and skin are the next most common sites. Only three cases have involved the testes, a sanctuary site. Of gastrointestinal sites, there are only a handful of cases with gastric involvement. In the pre-human antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, median overall survival was dismal. However, prognosis has improved since their advent. There is no significant difference in the survival of HIV-positive and HIV-negative PBL patients. It should be emphasized that due to the scarcity of cases, there are no established standards of care or prospective therapeutic trials for the management and treatment of PBL. Chemotherapy remains the standard approach, though selecting a regimen is still controversial and while response has been good, overall survival remains poor. Since 1995, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) has been the standard of care for relapsed chemosensitive HIV-negative NHL. In the era of HAART, this has become feasible for HIV patients. A few studies have suggested that use of AHCT in the first line setting and relapsed or refractory disease may confer better outcomes. Herein we describe a unique case of involvement in the testis and duodenum, and there are no previous reports of a patient presenting with both gastrointestinal and urogenital involvement.

Keywords: Plasmablastic lymphoma; Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; HIV

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare and highly aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). In the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, it is a distinct entity of B-cell lymphoma with “diffuse proliferation of large neoplastic cells most of which resemble B cell immunoblasts, but in which all tumor cells have a plasma cell immunophenotype” [1]. It was originally described in the oral cavity of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [2] but is also present in posttransplant patients [3, 4], elderly [5], immunosuppressed [6, 7] and immunocompetent patients [8, 9]. PBL accounts for about 2.6% of all AIDS-related lymphomas [10].

In the era before human antiretroviral therapy (HAART), median overall survival (OS) was 2.1 months [11]. However, prognosis has markedly improved since their advent [12-15]. There are over 300 reported cases of PBL, of which over 120 are present in HIV-positive patients. There is no significant difference in survival of HIV-positive and HIV-negative PBL patients. Overall median survival is 8 months but varies considerably (range 0 to 105 months). Overall, 62% of deceased patients died of lymphoma, while 12% died of sepsis and 6% multiorgan failure [16].

Due to the scarcity of cases, there are no established standards of care and no prospective therapeutic trials that have been done in patients with PBL.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 46-year-old Caucasian HIV-positive man, never on HAART, presented with 2 weeks of decreased PO intake, weight loss, increasing fatigue, and a swollen left testicle. On physical exam, he was cachectic with a BMI of 18.4, febrile, hypotensive, had oral thrush and a firm, non-tender, left testicular mass with inguinal lymphadenopathy. His fecal occult blood testing was positive. Complete blood count revealed critically severe microcytic anemia and thrombocytosis (MCV 66 fL, hemoglobin 4.6 g/dL, platelets 570 × 103/µL). Iron study labs suggested a multifactorial etiology for his anemia (Fe 16 µg/dL, TIBC 155 µg/dL, ferritin 89 ng/mL, transferrin 110 mg/dL). The patient was found to be hyponatremic (Na 131) and hypoalbuminemic (albumin 1.7 g/dL, prealbumin 4.4 mg/dL). His LDH level was markedly elevated (LDH 998 U/L). Blood cultures were negative.

Ultrasound showed a 3-cm hypervascular solid left testicular mass and multiple retroperitoneal masses of varying size. CT revealed a large, ulcerated, distal gastric mass, peritoneal carcinomatosis in the form of macroscopic peritoneal deposits and small volume ascites, and re-identified the known left intratesticular tumor, which measured 2.8 × 2.0 cm.

Evidence of an opportunistic infection and lack of HAART prompted further evaluation of his HIV status. He was found to have a CD4 count of 78/µL and viral load of 600,000 copies/mL. After consulting infectious disease, HAART, consisting of ritonavir, emtricitabine-tenofovir, and darunavir was initiated. Given a CD4 < 200, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim prophylaxis was started. HIV genotyping did not show any mutations, allowing the established HAART regimen to continue.

Upon admission, the patient was febrile without an established source of infection. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Chest X-ray on day 5 showed a right-sided pleural effusion with surrounding edema; vancomycin was started. A non-contrast CT was consistent with the chest X-ray and showed no evidence for pneumonia. The fevers resolved by day 11 and he was cleared for the OR.

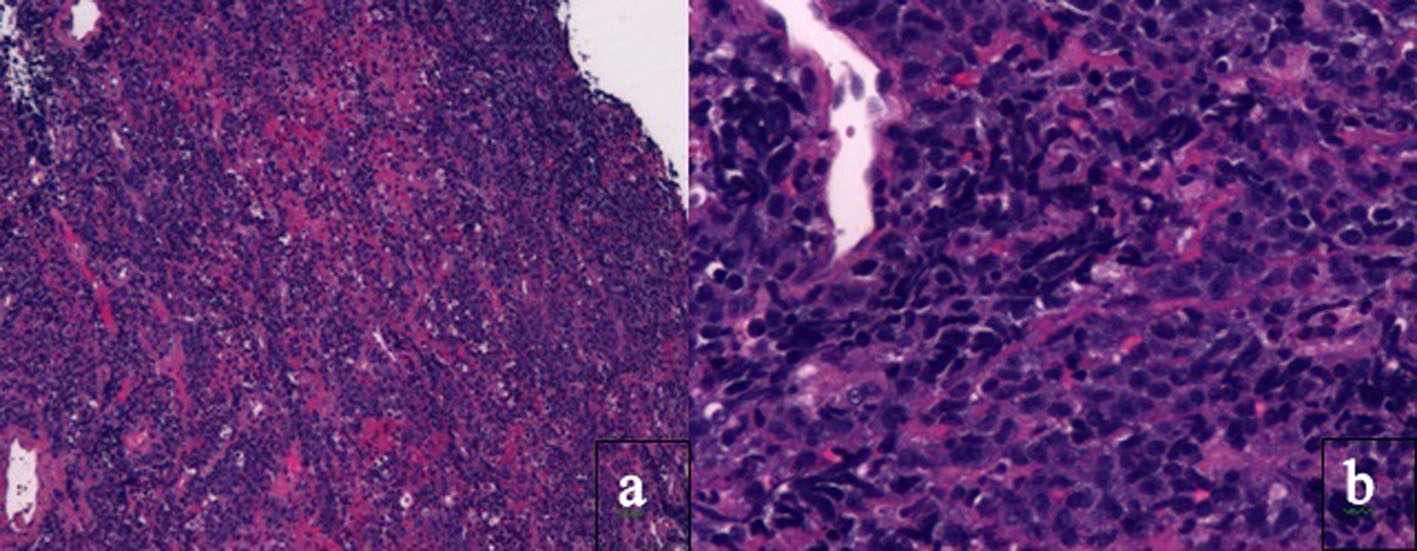

An upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy showed a large, fungating, ulcerated, circumferential mass in the body and antrum, partially obstructing the duodenum, which was biopsied. The pathology report revealed PBL and H. pylori (Fig. 1-3).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Histology of tissue biopsy of duodenum. Photomicrographs show the tumor in the duodenum under (a) low magnification × 4 and (b) high magnification × 20 on hematoxylin and eosin staining. PBL is characterized by monomorphic cellular proliferation of round or oval cells with centrally or eccentrically placed nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm in a diffuse growth pattern. Apoptotic bodies and mitotic figures and macrophages can lead to a starry sky appearance. |

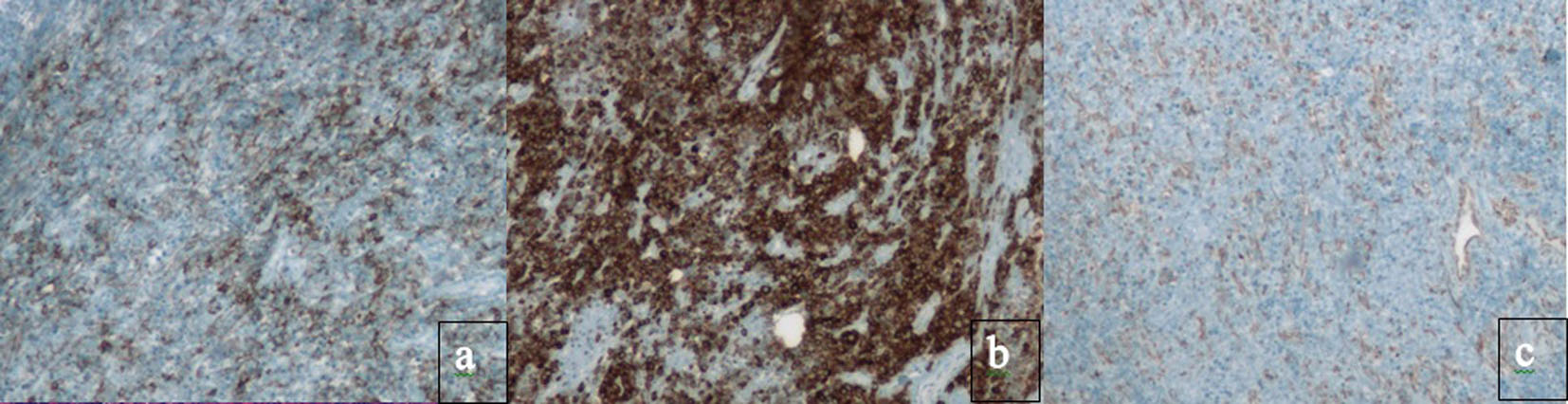

Click for large image | Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining absent in PBL. Classic B cell markers, such as CD20, CD79a, PAX-5 and CD45, are lost. Immunohistochemical staining for (a) CD20, (b) CD79a and (c) PAX-5. Instead, PBL has the immunophenotype of a terminally differentiated B cell. |

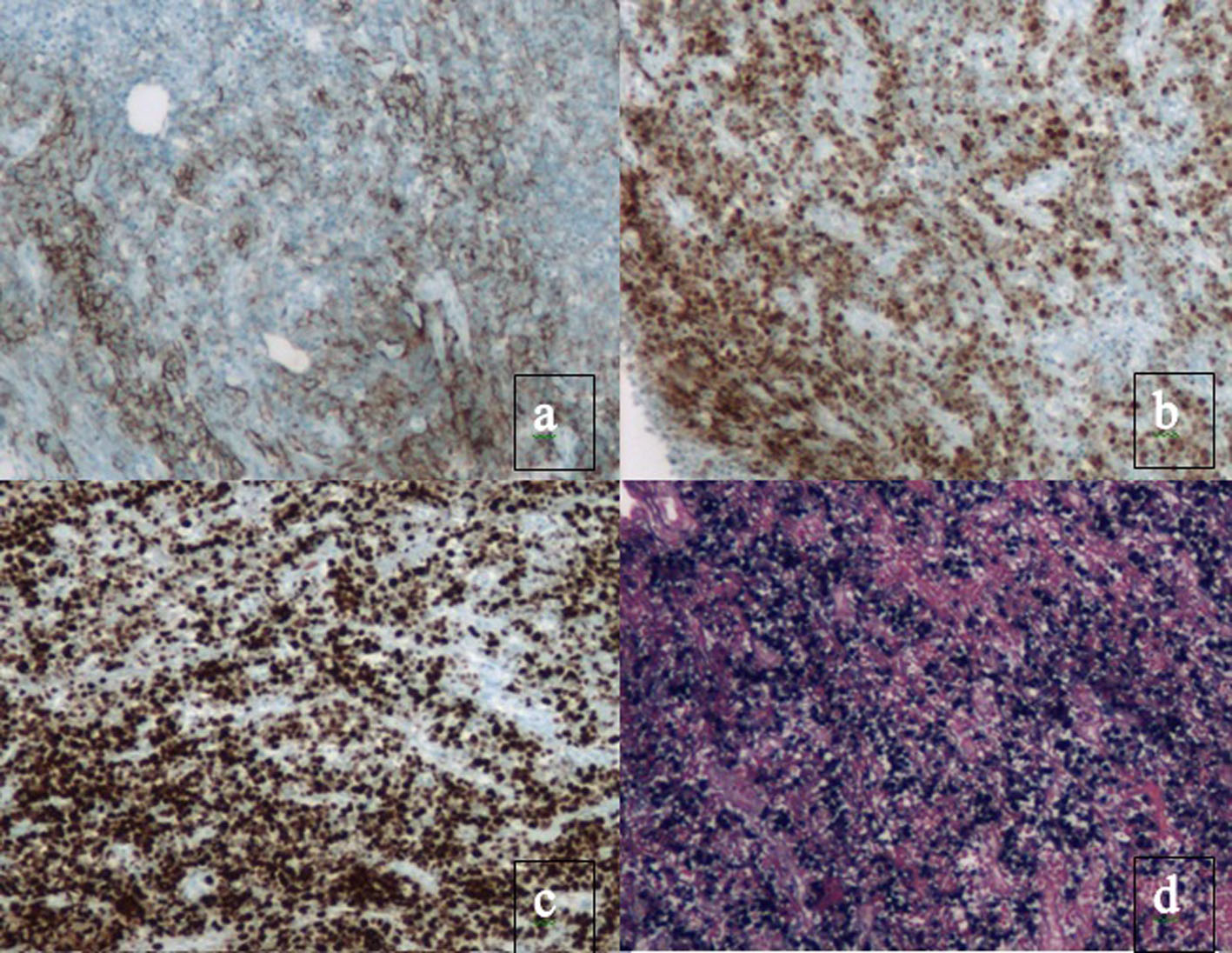

Click for large image | Figure 3. Immunohistochemical staining present in PBL. Plasma cell markers, such as CD38, CD138 and myeloma oncogene-1 (MUM1/IRF4) are expressed. There is also a high proliferation rate reflected by Ki67 expression > 80% and EBV present. Immunohistochemical staining for (a) CD138, (b) MUM1, (c) Ki67 and (d) EBER. |

Quadruple therapy was started for a 14-day course. Per recommendation of hematology oncology, IR-guided bone marrow biopsy and retroperitoneal biopsy were performed to stage the cancer. The patient had mild coagulopathy (PT 15.1 s, INR 1.3, PTT 40.4 s). Vitamin K was administered and workup revealed a minimal factor deficiency (factor 2: 0.58 U/mL, factor 10: 0.74 U/mL) which was attributed to cachexia and poor nutrition. The retroperitoneal biopsy was consistent with previously found gastric PBL, but the bone marrow biopsy was negative for lymphomatous involvement.

The testicular mass continued to enlarge over several days, resulting in tenderness and penile edema. The patient was amenable to a radical left orchiectomy. The pathology result of the testicular mass was consistent with PBL. Given the metastatic nature of his cancer and the involvement of a sanctuary site, hematology oncology recommended prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy prior to the initiation of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP). The patient received 12 mg intrathecal methotrexate with prednisone, which was well tolerated. He received his first course of R-CHOP during his admission. Follow-up with the HIV clinic and hematology was established prior to discharge.

Over the course of 6 months, the patient received six cycles of R-CHOP and prophylactic intrathecal methotrexate. Post-treatment PET/CT reveals marked residual PET-avidity in the region of the duodenum, highly concerning for persistence of lymphomatous disease at the site. Patient was referred to GI for direct visualization and biopsy of the hypermetabolic duodenal region. If this confirms residual disease, we will further discuss the optimal salvage regimen at that time.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Within 5 years of PBL first being described in 1992, the first case series of PBL in the oral cavity of HIV patients was published by Delecluse et al [2]. However, none of the patients in the case series were receiving HAART and the current wide spread utilization of HAART therapy may be contributing to the current wide distribution of sites of disease in cases of PBL. In addition there is the possibility that increased clinical suspicion has resulted in more PBL cases being diagnosed that otherwise would have gone undiagnosed or misdiagnosed [17].

In the two largest meta-analyses of over 200 reported cases of PBL, over 120 cases (50% and 69% respectively) were patients whom were HIV-positive [16, 18]. Of HIV-negative patients, 70% were immunocompetent and 28% were transplant recipients. The mean age of onset was 40 years and male/female ratio was 4.5:1. The primary sites were nodal (10 cases) and extranodal (117 cases) with majority of cases in the oral cavity (57 of 117), GI tract (21 of 117) and skin (13 of 117). Only three cases involved the urogenital tract, a sanctuary site [16, 19]. Of GI sites, there are six cases with stomach involvement (43%) [20]. Multiple organ involvement has also been noted [18, 21, 22]. PBL presents in advanced clinical stage, which is Ann Arbor Stage 3 or 4 [13, 16, 23]. There are no reports of a patient presenting with both a GI and a urogenital mass.

The pathogenesis of PBL is poorly understood but may be due to degree and duration of immunodeficiency, chronic antigenic stimulation or unresolved inflammatory state, EBV or gene rearrangement [24]. PBL is characterized by monomorphic cellular proliferation of round or oval cells with centrally or eccentrically placed nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm in a diffuse growth pattern. Apoptotic bodies and mitotic figures and macrophages can lead to a starry sky appearance [2].

PBL has the immunophenotype of a terminally differentiated B cell. Classic B cell markers, such as CD20, CD79a, PAX-5 and CD45, are lost. Plasma cell markers, such as CD38, CD138 and myeloma oncogene-1 (MUM1/IRF4) are expressed [23, 25, 26]. There is also a high proliferation rate reflected by Ki67 expression > 80%. Despite having an immunophenotype that resembles plasma cells, PBL has a genomic profile closer to diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [27, 28].

In patients with HIV-associated PBL, > 75% are EBV-positive [13, 16]. This observation may be explained by the hypothesis that EBV-positive lymphoma cells gradually lose EBV while accumulating genetic mutations resulting in a more aggressive phenotype or that it can trigger more effective immune responses. EBV-positive PBLs have a significantly better outcome compared to their EBV-negative counterparts. In the HIV+ population, EBV-positive cases have a reported mean survival of 13 months as opposed to 9 months in EBV-negative cases. In a review of all cases of PBL, EBV-positive survival was 14 months as opposed to 10 months in EBV-negative [16]. Patients with PBL who are not treated with chemotherapy have a median survival of 3 months [13]. Even with treatment, the most common cause of death in these patients is progression of their lymphoma. Retrospective studies demonstrate median progression free survival (PFS) and OS are 6 and 11 months, respectively [16, 17].

Prognostic factors associated with longer survival are early clinical stage and obtaining a complete response with chemotherapy. Use of HAART shows a trend towards statistical significance for better survival, potentially due to restoration of immune surveillance [5, 29, 30]. CD45 (partially expressed in 37% of cases) was associated with better outcomes, suggesting that the absence of CD45 may have prognostic implications [16].

Factors associated with worse outcomes are: age > 60 years, advanced stage at diagnosis, bone marrow involvement and lack of response with treatment [13]. Extraoral presentation sites tend to have decreased OS as compared to those with oral presentation. However, this observation was in a study with a small number of cases and requires validation with a larger group [31]. In addition, PBL with alteration of C-myc (57%) is associated with worse outcomes [16, 28, 32, 33].

The choice of initial chemotherapy regimen remains controversial and while response to a variety of regimens has been good, OS remains poor. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines indicate that “standard CHOP is not adequate therapy” and suggest treatment with intensified regimens, such as etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide (EPOCH), hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine (HyperCVAD) or cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC) [30]. Some studies have shown improved OS with EPOCH [34-36]. It should be emphasized that although the complete response rate is over 60%, many case series and reviews show no benefits with regards to PFS or OS when comparing treatment with CHOP versus more intensified regimens such as EPOCH [17, 29].

Intrathecal prophylaxis is a mandatory part of systemic treatment as HIV-associated PBLs are at risk for leptomeningeal disease. Either methotrexate or cytarabine can be used [37, 38]. Several case reports describe bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor with activity in multiple myeloma, as an active agent in relapsed PBL [39-42].

The outcome for relapsed PBL is dismal. A few studies have suggested that use of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) in the first line setting and relapsed or refractory disease may confer better outcomes [5, 40, 43]. Since 1995, AHCT has been the standard of care for relapsed chemosensitive HIV-negative NHL [44]. In the era of HAART, this has become feasible for HIV patients [45].

In the literature, there are 25 patients with HIV and relapsed PBL who received AHCT [12, 43]. In three patients, 81% achieved PFS at 2 years [45-47]. Another study of four patients had 56.5% PFS at 3 years [4]. Another two patients treated with AHCT after induction with CHOP resulted in complete response at 83 months while the other progressed and died 4 months after AHCT [12]. Other studies have shown similar outcomes [48]. However, up to 60% of patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoma will progress before reaching AHCT [43, 49, 50].

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (AlloHCT) had limited success due to significant exposure to opportunistic infection, high incidence of concomitant infections and complex drug-drug interactions [43]. In 2009, an HIV-positive man with PBL was noted to be alive over 2 years after AlloHCT [51]. Since there are still limited studies in this area, more is needed before further evaluation.

Conclusions

PBL is a rare disease with around 120 cases in the HIV population. While common sites are the GI tract and skin, we describe the only case of involvement in both the duodenum and testis. Although our patient has received chemotherapy for six cycles, he appears to have persistent disease. OS is minimally improved for these patients despite the advent of HAART and chemotherapy. While salvage chemotherapy could be offered in refractory setting, the options are limited and this patient’s survival appears poor. In the era of HAART, use of AHCT in the first line setting and relapsed or refractory disease may confer better outcomes. Further study of AHCT, established standards of care and prospective therapeutic trials are warranted in this population.

Abbreviations

NHL: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; AHCT: autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation; PBL: plasmablastic lymphoma; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; WHO: World Health Organization; AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HAART: human antiretroviral therapy; R-CHOP: rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; EPOCH: etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide; HyperCVAD: hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with methotrexate and cytarabine; CODOX-M/IVAC: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, cytarabine; AlloHCT: allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation

| References | ▴Top |

- Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphomas: implications for clinical practice and translational research. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:523-531.

doi pubmed - Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, Hummel M, Marafioti T, Schneider U, Huhn D, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89(4):1413-1420.

pubmed - Morscio J, Dierickx D, Tousseyn T. Molecular pathogenesis of B-cell posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder: what do we know so far? Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:150835.

- Balsalobre P, Diez-Martin JL, Re A, Michieli M, Ribera JM, Canals C, Rosselet A, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with HIV-related lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(13):2192-2198.

doi pubmed - Liu JJ, Zhang L, Ayala E, Field T, Ochoa-Bayona JL, Perez L, Bello CM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative plasmablastic lymphoma: a single institutional experience and literature review. Leuk Res. 2011;35(12):1571-1577.

doi pubmed - Wang HW, Yang W, Sun JZ, Lu JY, Li M, Sun L. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the small intestine: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(45):6677-6681.

doi pubmed - Chen DB, Song QJ, Chen YX, Chen YH, Shen DH. Clinicopathologic spectrum and EBV status of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2013;97(1):117-124.

doi pubmed - Huang X, Zhang Y, Gao Z. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the stomach with C-MYC rearrangement in an immunocompetent young adult: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(4):e470.

doi pubmed - Ustun C, Reid-Nicholson M, Nayak-Kapoor A, Jones-Crawford J, McDonald K, Jillella AP, Ramalingam P. Plasmablastic lymphoma: CNS involvement, coexistence of other malignancies, possible viral etiology, and dismal outcome. Ann Hematol. 2009;88(4):351-358.

doi pubmed - Carbone A, Gloghini A. Plasmablastic lymphoma: one or more entities? Am J Hematol. 2008;83(10):763-764.

doi pubmed - Tirelli U, Errante D, Spina M, Gastaldi R, Nigra E, Nosari AM, Magnani G, et al. Second-line chemotherapy in human immunodeficiency virus-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: evidence of activity of a combination of etoposide, mitoxantrone, and prednimustine in relapsed patients. Cancer. 1996;77(10):2127-2131.

doi - Cattaneo C, Finel H, McQuaker G, Vandenberghe E, Rossi G, Dreger P. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for plasmablastic lymphoma: the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation experience. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(6):1146-1147.

doi pubmed - Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, Perez K, Jabbour M, Milani C, Colvin G, et al. Clinical and pathological differences between human immunodeficiency virus-positive and human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with plasmablastic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(11):2047-2053.

doi pubmed - Guan B, Zhang X, Ma H, Zhou H, Zhou X. A meta-analysis of highly active anti-retroviral therapy for treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2010;3(1):7-12.

doi - Palella FJ, Jr., Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853-860.

doi pubmed - Morscio J, Dierickx D, Nijs J, Verhoef G, Bittoun E, Vanoeteren X, Wlodarska I, et al. Clinicopathologic comparison of plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive, immunocompetent, and posttransplant patients: single-center series of 25 cases and meta-analysis of 277 reported cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(7):875-886.

doi pubmed - Castillo JJ, Furman M, Beltran BE, Bibas M, Bower M, Chen W, Diez-Martin JL, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5270-5277.

doi pubmed - Rafaniello Raviele P, Pruneri G, Maiorano E. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a review. Oral Dis. 2009;15(1):38-45.

doi pubmed - Dong HY, Scadden DT, de Leval L, Tang Z, Isaacson PG, Harris NL. Plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive patients: an aggressive Epstein-Barr virus-associated extramedullary plasmacytic neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(12):1633-1641.

doi pubmed - Luria L, Nguyen J, Zhou J, Jaglal M, Sokol L, Messina JL, Coppola D, et al. Manifestations of gastrointestinal plasmablastic lymphoma: a case series with literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(33):11894-11903.

doi pubmed - Liang R, Wang Z, Chen XQ, Bai QX. Treatment of plasmablastic lymphoma with multiple organ involvement. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(12):e194-197.

doi pubmed - Tavora F, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Sun CC, Burke A, Zhao XF. Extra-oral plasmablastic lymphoma: report of a case and review of literature. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(9):1233-1236.

doi pubmed - Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, Foss RD. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10(1):8-12.

doi pubmed - Bibas M, Castillo JJ. Current knowledge on HIV-associated Plasmablastic Lymphoma. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6(1):e2014064.

doi pubmed - Carbone A, Vaccher E, Gloghini A, Pantanowitz L, Abayomi A, de Paoli P, Franceschi S. Diagnosis and management of lymphomas and other cancers in HIV-infected patients. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(4):223-238.

doi pubmed - Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(10):804-809.

doi pubmed - Chang CC, Zhou X, Taylor JJ, Huang WT, Ren X, Monzon F, Feng Y, et al. Genomic profiling of plasmablastic lymphoma using array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH): revealing significant overlapping genomic lesions with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:47.

doi pubmed - Taddesse-Heath L, Meloni-Ehrig A, Scheerle J, Kelly JC, Jaffe ES. Plasmablastic lymphoma with MYC translocation: evidence for a common pathway in the generation of plasmablastic features. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(7):991-999.

doi pubmed - Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, Perez K, Jabbour M, Milani C, Colvin G, et al. Prognostic factors in chemotherapy-treated patients with HIV-associated Plasmablastic lymphoma. Oncologist. 2010;15(3):293-299.

doi pubmed - Teruya-Feldstein J, Chiao E, Filippa DA, Lin O, Comenzo R, Coleman M, Portlock C, et al. CD20-negative large-cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogenous spectrum in both HIV-positive and -negative patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(11):1673-1679.

doi pubmed - Hansra D, Montague N, Stefanovic A, Akunyili I, Harzand A, Natkunam Y, de la Ossa M, et al. Oral and extraoral plasmablastic lymphoma: similarities and differences in clinicopathologic characteristics. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(5):710-719.

doi pubmed - Valera A, Balague O, Colomo L, Martinez A, Delabie J, Taddesse-Heath L, Jaffe ES, et al. IG/MYC rearrangements are the main cytogenetic alteration in plasmablastic lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(11):1686-1694.

doi - Bogusz AM, Seegmiller AC, Garcia R, Shang P, Ashfaq R, Chen W. Plasmablastic lymphomas with MYC/IgH rearrangement: report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132(4):597-605.

doi pubmed - Barta SK, Xue X, Wang D, Tamari R, Lee JY, Mounier N, Kaplan LD, et al. Treatment factors affecting outcomes in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a pooled analysis of 1546 patients. Blood. 2013;122(19):3251-3262.

doi pubmed - Little RF, Pittaluga S, Grant N, Steinberg SM, Kavlick MF, Mitsuya H, Franchini G, et al. Highly effective treatment of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma with dose-adjusted EPOCH: impact of antiretroviral therapy suspension and tumor biology. Blood. 2003;101(12):4653-4659.

doi pubmed - Sparano JA, Lee JY, Kaplan LD, Levine AM, Ramos JC, Ambinder RF, Wachsman W, et al. Rituximab plus concurrent infusional EPOCH chemotherapy is highly effective in HIV-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115(15):3008-3016.

doi pubmed - Bilgrami M, O'Keefe P. Neurologic diseases in HIV-infected patients. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;121(1321-1344.

- Spina M, Chimienti E, Martellotta F, Vaccher E, Berretta M, Zanet E, Lleshi A, et al. Phase 2 study of intrathecal, long-acting liposomal cytarabine in the prophylaxis of lymphomatous meningitis in human immunodeficiency virus-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2010;116(6):1495-1501.

doi pubmed - Bibas M, Grisetti S, Alba L, Picchi G, Del Nonno F, Antinori A. Patient with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma responding to bortezomib alone and in combination with dexamethasone, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, cytarabine, and pegfilgrastim chemotherapy and lenalidomide alone. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(34):e704-708.

doi pubmed - Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Czuczman MS, Dave SS, Wright G, Grant N, Shovlin M, et al. Differential efficacy of bortezomib plus chemotherapy within molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2009;113(24):6069-6076.

doi pubmed - Lipstein M, O'Connor O, Montanari F, Paoluzzi L, Bongero D, Bhagat G. Bortezomib-induced tumor lysis syndrome in a patient with HIV-negative plasmablastic lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010;10(5):E43-46.

doi pubmed - Saba NS, Dang D, Saba J, Cao C, Janbain M, Maalouf B, Safah H. Bortezomib in plasmablastic lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Onkologie. 2013;36(5):287-291.

doi pubmed - Al-Malki MM, Castillo JJ, Sloan JM, Re A. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for plasmablastic lymphoma: a review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(12):1877-1884.

doi pubmed - Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Somers R, Van der Lelie H, Bron D, Sonneveld P, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(23):1540-1545.

doi pubmed - Krishnan A, Palmer JM, Zaia JA, Tsai NC, Alvarnas J, Forman SJ. HIV status does not affect the outcome of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(9):1302-1308.

doi pubmed - Krishnan A, Molina A, Zaia J, Nademanee A, Kogut N, Rosenthal J, Woo D, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for HIV-associated lymphoma. Blood. 2001;98(13):3857-3859.

doi pubmed - Krishnan A, Molina A, Zaia J, Smith D, Vasquez D, Kogut N, Falk PM, et al. Durable remissions with autologous stem cell transplantation for high-risk HIV-associated lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105(2):874-878.

doi pubmed - Vose JM, Rizzo DJ, Tao-Wu J, Armitage JO, Bashey A, Burns LJ, Christiansen NP, et al. Autologous transplantation for diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma in first relapse or second remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10(2):116-127.

doi pubmed - Re A, Michieli M, Casari S, Allione B, Cattaneo C, Rupolo M, Spina M, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation as salvage treatment for AIDS-related lymphoma: long-term results of the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors (GICAT) study with analysis of prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;114(7):1306-1313.

doi pubmed - Serrano D, Carrion R, Balsalobre P, Miralles P, Berenguer J, Buno I, Gomez-Pineda A, et al. HIV-associated lymphoma successfully treated with peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(4):487-494.

doi pubmed - Hamadani M, Devine SM. Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation in HIV patients with hematologic malignancies: yes, we can. Blood. 2009;114(12):2564-2566.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.