| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 8, Number 4, December 2019, pages 160-164

Delayed Presentation of Thymoma-Related Aplastic Anemia: An Unusual Presentation of a Rare Complication

Kathrin Dvira, c, Gliceida M. Galarza Fortunaa, Michael Schwartzb

aDepartment of Internal Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL, USA

bMount Sinai Comprehensive Cancer Center, Miami Beach, FL, USA

cCorresponding Author: Kathrin Dvir, Department of Internal Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL 33140, USA

Manuscript submitted August 24, 2019, accepted October 7, 2019

Short title: Delayed Presentation of TR-AA

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh557

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A 68-year-old Caucasian man presented with gross hematuria and oral mucosal bleeding. The patient was known to have an anterior mediastinal mass, highly suspicious for thymoma, which was incidentally identified on imaging, 8 years prior. The patient then declined treatment and was lost to follow-up. On presentation, imaging re-demonstrated the anterior mediastinal mass and the patient was found to have profound pancytopenia. Bone marrow biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of aplastic anemia (AA). Despite optimal treatment, the patient expired on day 9 of admission. In this case we report an unusual presentation of thymoma-related AA (TR-AA), a rare complication of thymoma, presenting years after initial diagnosis in a patient with long standing thymoma that was left untreated as per the patient’s wishes. To our best knowledge, this is the first published report where TR-AA presented 8 years after initial diagnosis in a patient with unresected and untreated thymoma.

Keywords: Thymoma; Aplastic anemia; Delayed presentation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Thymoma is a rare tumor. Its incidence in the USA is 0.13 per 100,000 person-years [1]. Thymoma-related aplastic anemia (TR-AA) is one of the rarest complications of thymoma, with incidences ranging between 0% and 1.4% [2].

In about two-thirds of cases, TR-AA presents concomitantly or immediately prior to the discovery of thymoma [2, 3], often leading to its diagnosis. In this report we describe a rare case of TR-AA appearing years after the thymoma was incidentally found in a previously asymptomatic patient with no abnormalities of blood count and with an 8-year history of untreated anterior mediastinal mass.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 68-year-old Caucasian man with a history of an anterior mediastinal mass suspicious for thymoma that was identified on chest imaging 8 years prior, for which the patient declined surgery, presented to the emergency department with gross hematuria and oral mucosal bleeding. The patient also endorsed a 1-month history of generalized weakness, fatigue, subjective fever and a 7-kg unintentional weight loss. The patient stated that over the preceding 8 years he was generally in a good health, with no significant health issues; however, he admitted that he had not been to a doctor or had any blood test done. He denied taking any medications, vitamins or supplements. He admitted an infrequent alcohol consumption, but denied recreational drug use. On presentation, he was found to have marked pancytopenia and was immediately started on broad spectrum antibiotics and transfused with red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets.

On day 1, complete blood count revealed marked pancytopenia with severe thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and inappropriately low retic count. The patient’s last complete blood count on record was dated to 8 years prior and was within normal limits. Imaging re-demonstrated mediastinal mass with interval enlargement, interpreted again as likely thymoma versus invasive thymoma. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, transfused with platelets, RBCs and started on vancomycin, piperacillin/tazobactam and intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone.

On day 2, bone marrow biopsy findings supported the diagnosis of severe AA. Cyclosporine, eltrombopag and anti-thymocyte globulin were added, with planned thymoma resection, upon stabilization.

On days 3 - 4, platelets count improved; however, absolute neutrophil count remained extremely low, necessitating starting posaconazole and acyclovir, prophylactically.

On days 5 - 6, the patient developed transient sudden loss of consciousness while supine, associated with hypotension and oxygen desaturation. Stroke alert called; however, computed tomography (CT) brain was negative for acute intracranial process. Later that day, a new 5- to 6-cm right maxillary swelling was noted.

On days 7 - 8, maxillary swelling increased to 10 cm, impeding respiration. The patient was intubated and sedated. Ear, nose and throat (ENT) and interventional radiology agreed on self-tamponade as most appropriate approach for the rapidly expanding maxillary swelling.

On day 9, blood cultures were positive for Gram-negative rods (Enterobacter cloaceae) and Fungemia. Cefepime and micafungin were started. Patient developed multiorgan failure and made do not resuscitate (DNR) at family’s request. Cardiopulmonary arrest occurred later that day and the patient expired. No post-mortem examination was done due to family’s refusal.

Investigations

Upon admission, the patient was found to have profound pancytopenia: white blood cells (WBCs) 1.63 × 103/µL (reference range 4.80 - 10.80), absolute neutrophil count 0.02 × 103/µL (reference range 1.80 - 7.20), RBCs 2.75 × 106/µL (reference range 4.63 - 6.08), platelets < 2 × 103/µL (reference range 150 - 450), hemoglobin 8.5 g/dL (reference range 14.0 - 18.0) and reticulate count of 0.38% (reference range 0.54 - 2.10).

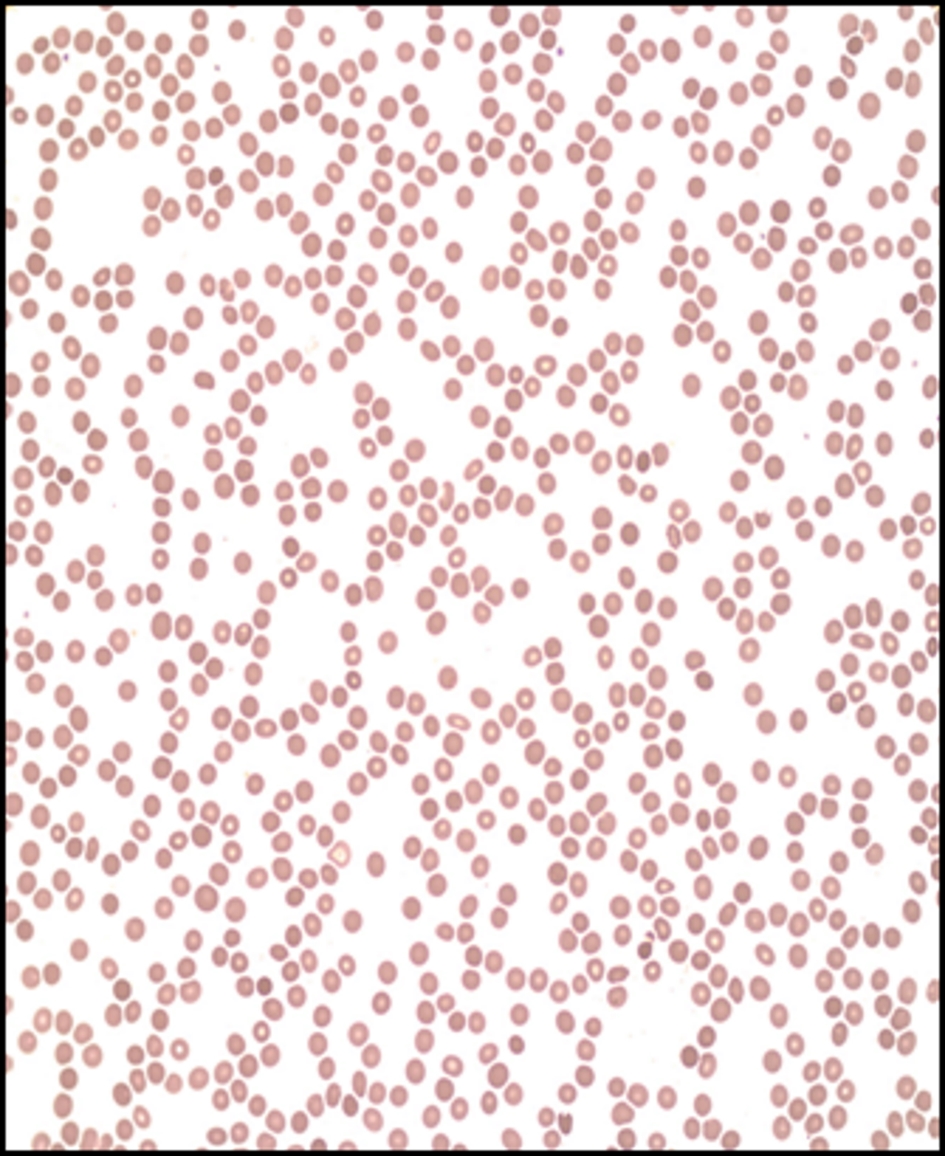

Comparably, peripheral blood smear (Fig. 1) showed markedly reduced RBCs, platelets, and leukocytes. There was mild anisocytosis without significant morphological abnormalities.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Peripheral blood smear. Markedly reduced red blood cells, platelets, and leukocytes. Mild anisocytosis without significant morphological abnormalities. |

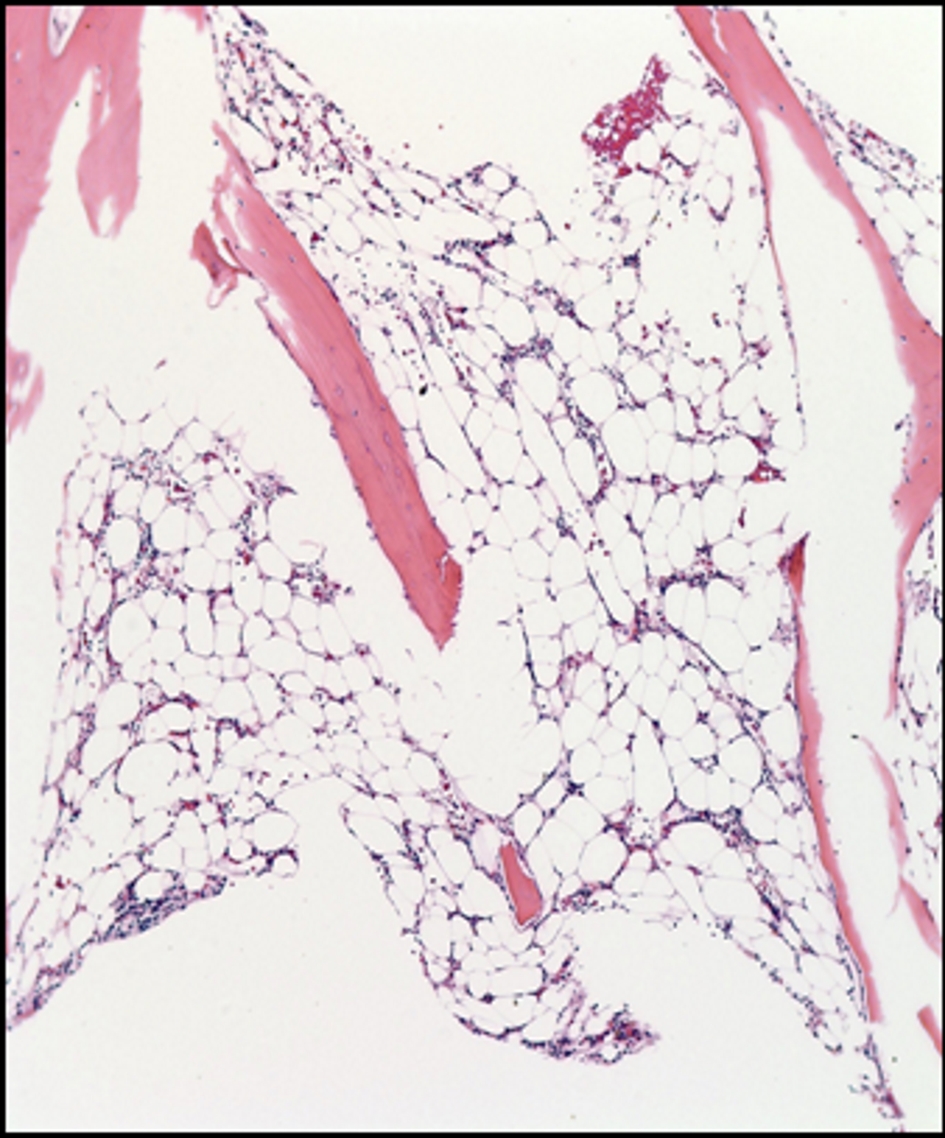

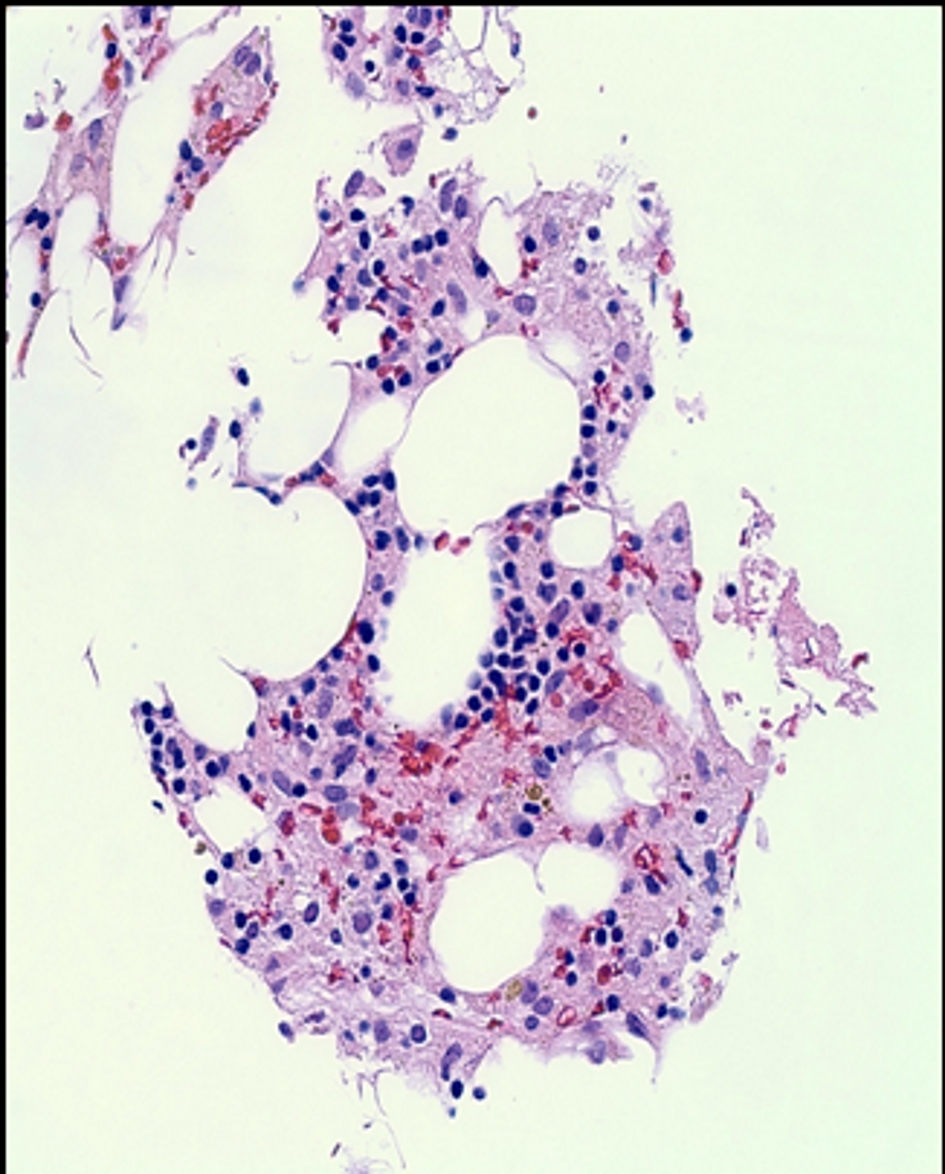

Patient consequently underwent bone marrow biopsy (Fig. 2) revealing profound hypocellularity of 5% (expected for age 25-30%) with decreased numbers in all hematopoietic lineages and bone marrow aspirate (Fig. 3) showing no evidence of dysplasia. Residual cells including few lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, some containing hemosiderin, were seen in the bone marrow fat.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Bone marrow biopsy. The bone marrow shows profound hypocellularity of 5% (expected for age 25-30%) with decreased numbers in all hematopoietic lineages. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Bone marrow aspirate. There was no evidence of dysplasia. Residual cells including few lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, some containing hemosiderin, were seen in the bone marrow fat. |

Hemolytic uremic syndrome/thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (HUS/TTP) screening labs were negative: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was consistently normal at 108 U/L and 133 on repeat testing after 48 h (normal range 84 - 246). Haptoglobin was elevated at 419 mg/dL (normal range 30 - 200) and fibrinogen was 724 mg/dL (normal range 200 - 400). Direct bilirubin was elevated at 0.4 mg/dL (0.05 - 0.2). However, the patient did not exhibit any diarrhea or hematochezia.

Renal function test revealed elevated creatinine at 1.31 mg/dL (0.7 - 1.30) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 46 mg/dL (7 - 18). Both improved after hydration. All electrolytes were within normal limits.

For microbiology, urine cultures were consistently negative on several occasions. Initial blood cultures were negative until day 9 of admission when cultures grew Enterobacter cloaceae and fungal elements were seen. Blood cultures remained negative for acid-fast bacilli. Given that the patient had a recent history of hiking in a tick-infested area, Lyme disease and Ehrlichia chaffeensis were suspected; however, antibodies screening resulted negative.

For rheumatological testing, complement C3 was normal at 124 mg/dL (normal range 90 - 180), and C4 slightly elevated at 39 mg/dL (normal range 10 - 40). Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) screening were negative, myasthenia-related anti-Ach antibodies resulted negative and no antibodies were detected for myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3 antibodies. Vitamin B12 levels were normal at 553 PG/mL (normal range 193 - 986).

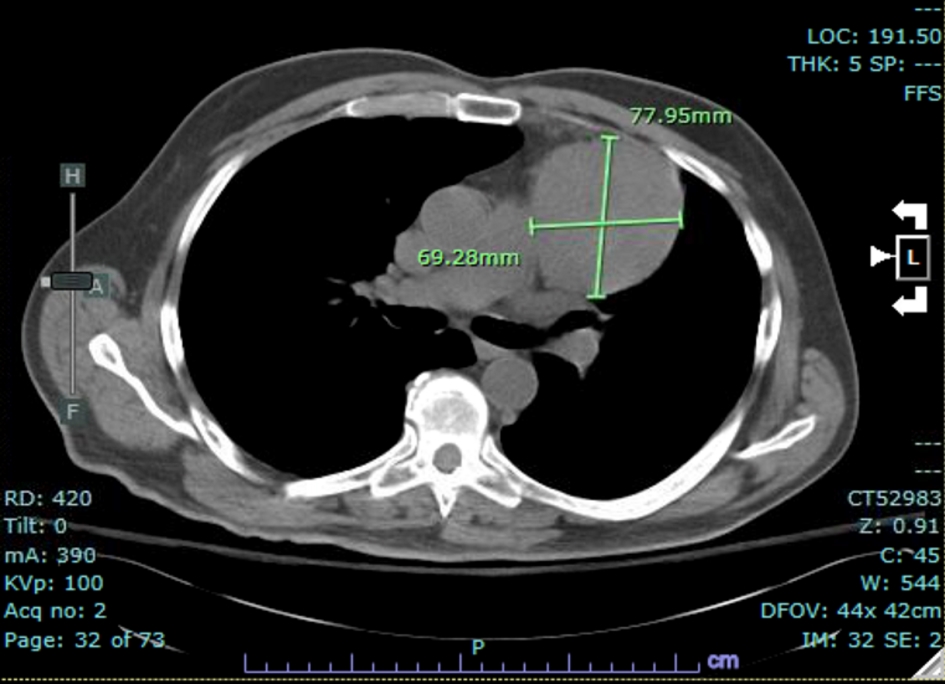

Imaging studies re-demonstrated the left anterior mediastinal mass that was known 8 years prior to presentation, on both chest X-ray (Fig. 4) and on non-contrast CT (Fig. 5). CT chest, abdomen and pelvis showed interval enlargement of anterior mediastinal mass, measuring 7.8 × 6.9 cm, from previously measured 4.7 × 4.3 cm on positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) done 8 years prior. These findings likely represented a thymoma versus potential invasive thymoma.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Chest X-ray: 8.0 × 7.5 cm left anterior mediastinal mass. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. CT of the chest: interval enlargement of anterior mediastinal mass measuring 7.8 × 6.9 cm. CT: computed tomography. |

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of an AA in the setting of anterior mediastinal mass mostly suggests TR-AA. Nevertheless, considering that the AA was not present at the time of the thymoma discovery, as it usually does [2, 3], other causes were considered.

The differential diagnosis of an acquired AA is broad; however, a newly diagnosed AA in the setting of an anterior mediastinal mass would most likely represent TR-AA. Nevertheless, given the atypical timeline of presentation, other primary causative culprits were considered.

Pancytopenia with predominantly severe thrombocytopenia, acute kidney injury, with hematuria and proteinuria suggested HUS/TTP as a plausible diagnosis.

As specified in the investigation section above, the patient was worked for possible HUS/TTP, leukemia, myelodysplasia, and multiple myeloma. Rheumatological panel was performed to exclude autoimmune conditions known to be associated with AA (i.e. systemic lupus erythematosus-related pancytopenia, myasthenia gravis, etc.). Finally infective agents were considered; however, all serological testing and initial cultures as specified above resulted negative.

Conversely, the differential diagnosis of an anterior mediastinal mass in the setting of bone marrow suppression is narrower. Most anterior mediastinal masses would likely represent thymoma; however, since definitive diagnosis via biopsy was never achieved in our patient, additional differentials for mediastinal mass would include other thymic tumors (thymic carcinoma, thymic cyst), lymphoma (non-Hodgins’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and thyroid masses. These options were effectively ruled out by a non-suggestive clinical presentation, imaging, labs and bone marrow biopsy that did not show any signs of dysplasia or malignant cells.

Outcome

This is a case of a fatal TR-AA despite optimal treatment as per current knowledge [2-6].

Upon presentation and immediate recognition of severe pancytopenia, the patient was started on high-dose systemic steroids, cyclosporine, eltrombopag and anti-thymocyte globulin in addition to broad spectrum antibiotics. He was repeatedly transfused with RBCs and platelets and treated supportively in the intensive care unit. However, despite optimal therapy, on day 5 of admission, the patient developed AA-related complications arising from severe thrombocytopenia and neutropenia.

A rapidly expanding soft tissue neck swelling was noted, which impeded respiration and necessitated emergent endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation. Shortly after, the patient developed bacteremia and fungemia. The antibiotics were adjusted to the cultures; however, despite all efforts, the patient developed septic shock with multiorgan failure which led to cardiopulmonary arrest.

As per the family’s wishes the patient was not taken for post-mortem examination.

Despite the dire outcome, this case should be noted for the a successful collaboration between a multitude of consulting professionals, as part of the multidisciplinary team; hematology, cardiothoracic surgery, infectious disease, interventional radiology, ENT, nephrology, intensivist and palliative care were working together in order to treat the patient in the most safe and efficacious manner, in the complex circumstances of diagnostic uncertainly amid preserving the ethical principles of non-maleficence and benefices.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

TR-AA is a rare, T-cell mediated autoimmune disorder (AD), which presents in patients with thymoma [1-3]. TR-AA is often fatal; however, a prompt diagnosis and treatment might result in favorable outcomes [2, 4-6]. Although TR-AD usually precedes the discovery of thymoma or presents concomitantly, often leading to its diagnosis [3], several cases have been described in which TR-AA presented after thymoma eradication [4-7]. However, to our best knowledge, this is the first published case where a very severe TR-AA occurred in the presence of long standing, neglected thymoma, years after its incidental discovery.

At initial diagnosis, the tumor measured 4.7 × 4.3 cm and there were no hematological abnormalities seen on patient’s complete blood count tests. The patient then declined all treatment and was lost to follow-up. Eight years later, the patient presented with severe TR-AA with his thymoma doubled in size to 7.8 × 7.0 cm. There were no other identified causes that might explain patient’s acquired AA, including medications, toxins, infections or autoimmune diseases.

Extensive literature search did not reveal any links between the size of the tumor or its resection status and the risk of developing TR-AA. In fact, there were reports of TR-AD, including TR-AA, presenting after complete thymoma eradication [5], but no reports of TR-AA in the presence of unresected tumor, years after its initial diagnosis.

In this case report we described an unusual presentation of a rare complication, with its exact triggering factor remaining unidentified.

It is difficult to draw practical conclusions for such rare complication. However given the frequently fatal nature of TR-AA and the importance of prompt treatment initiation to improve outcome, perhaps a periodical screening using complete blood count test should be considered in patients with a history of thymoma.

Learning point and take-home messages

TR-AA is a rare and often fatal complication of thymoma [1, 7].

In most cases, TR-AA presents at the time of thymoma diagnosis; however, as described in this case report, a very late presentation is possible [2, 3].

Eradication of the thymoma does not seem to prevent the development of TR-AA [4, 5].

Early recognition and treatment of TR-AA might improve outcome [2, 4-6].

There might be a role for AA screening via periodical complete blood count tests in patients with a history of thymoma.

Acknowledgments

We would to acknowledge the multidisciplinary team at Mount Sinai Medical Center of Florida who were involved in the care of the patient described in this manuscript.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

KD and MS were both primary clinicians in the care of the described patient. Both have been involved in the drafting of this manuscript and revising it critically in preparation for publishing. GMGF helped to write the manuscript, review and proof read it

| References | ▴Top |

- Engels EA. Epidemiology of thymoma and associated malignancies. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(10 Suppl 4):S260-265.

doi pubmed - Gaglia A, Bobota A, Pectasides E, Kosmas C, Papaxoinis G, Pectasides D. Successful treatment with cyclosporine of thymoma-related aplastic anemia. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(4C):3025-3028.

- Bernard C, Frih H, Pasquet F, Kerever S, Jamilloux Y, Tronc F, Guibert B, et al. Thymoma associated with autoimmune diseases: 85 cases and literature review. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(1):82-92.

doi pubmed - Ritchie DS, Underhill C, Grigg AP. Aplastic anemia as a late complication of thymoma in remission. Eur J Haematol. 2002;68(6):389-391.

doi pubmed - Bajel A, Ryan A, Roy S, Opat SS. Aplastic anaemia: autoimmune sequel of thymoma. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(5):591.

doi pubmed - Chintakuntlawar AV, Rizvi SA, Cassivi SD, Pardanani A. Thymoma-associated pancytopenia: immunosuppressive therapy is the cornerstone for durable hematological remission. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(3):453-458.

doi pubmed - Arcasoy MO, Gockerman JP. Aplastic anaemia as an autoimmune complication of thymoma. Br J Haematol. 2007;137(4):272.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.