| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.thejh.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 5, October 2022, pages 176-184

Oral Chemotherapy Application in Elderly Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: An Alternative Regimen in Retrospective Analysis

Pi-Han Liaoa , Ching-Yuan Kuoa, b, Ming-Chun Maa, Chin-Kai Liaoa, c, Sung-Nan Peia, c, Ming-Chung Wanga, d

aDivision of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, Republic of China

bKaohsiung Municipal Feng-Shan Hospital, Taiwan, Republic of China

cDepartment of Hematology, E-Da Cancer Hospital and I-Shou University, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, Republic of China

dCorresponding Author: Ming-Chung Wang, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung City 833401, Taiwan, Republic of China

Manuscript submitted September 11, 2022, accepted October 14, 2022, published online October 31, 2022

Short title: Oral Chemotherapy in Elderly With DLBCL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh1054

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: A combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) is considered the standard treatment for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). However, no standard treatment has been established for older patients (age ≥ 75 years). This study retrospectively analyzed different treatment strategies in older patients with DLBCL with different chemotherapy regimens and compared the survival rate of patients using oral or intravenous form cyclophosphamide and etoposide in a single center.

Methods: We reviewed the records of older patients with DLBCL, aged ≥ 75 years, from January 2010 to August 2019. The different treatment combinations, clinical characteristics, response rates, and toxicity profiles were analyzed. The median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method. Cox regression model was used to identify the risk factors.

Results: Eighty-four patients were included. One-quarter of the patients received cytoreduction treatment because of their poor medical condition at the time of diagnosis. Twenty-six percent of the patients were aged ≥ 85 at the time of diagnosis and 46.7% completed the treatment course. Patients receiving non-anthracycline-containing (non-ACR) treatment had worse Charlson comorbidity index, worse PFS, lower body mass index, or were older. The mean anthracycline accumulative dose in the anthracycline-containing (ACR) group was 134 mg/m2. The median OS was 17.2 months and median PFS was 7.7 months. The PFS of R-CHOP is better than R-mini-CHOP and R-CVOP without statistical significance, but OS of R-CHOP is not better than the other regimens.

Conclusion: The toxicity, efficacy, and KM curve for OS and PFS in the non-ACR group were lower compared to ACR group, without statistical significance. R-CVOP had similar OS with R-mini-CHOP in our study. The result does not mean etoposide could totally substitute for anthracycline, but etoposide did have lower early progression rate (12.5%), and it may be an option for frail patients with comorbidity. Oral form cyclophosphamide and etoposide could be considered as a substitute for intravenous administration because of the similar effect and toxic profile.

Keywords: Elderly; Anthracycline-free; Etoposide; DLBCL; R-CHOP

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and accounts for 50% of lymphoid malignancies in Taiwan [1]. If left untreated, the median survival of patients with DLBCL is less than 12 months [2, 3]. The median age at diagnosis is 67 years, and approximately one-third of the patients are diagnosed after the age of 70 [4]. In an aging society, the population older than 75 years is expected to triple by 2030; therefore, older patients with DLBCL will quickly account for a substantial proportion of oncology patients [2, 4-6]. According to 2014 Medicare-SEER data, 33% of patients with DLBCL who are older than 80 do not receive treatment for a potentially curable malignancy and only account for < 10% of the population in clinical trials [3, 5]. Although a combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) is still the standard of care for the majority of DLBCL cases, there are no widely accepted guidelines for the care of older patients [7-9]. Attenuation of chemotherapy doses or substitution of alternative drugs for doxorubicin due to concerns about cardiotoxicity occurs very often [10-12].

This study aimed to compare the overall survival (OS) and clinical characteristics of older patients with DLBCL under different treatment regimens and compared intravenous (IV) and oral formed chemotherapies. Furthermore, the remission rate, toxicity profiles, and progression-free survival (PFS) among the different combo regimens were compared. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to investigate the relationships between several factors and survival.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Patients

The study included patients aged ≥ 75 years with histologically confirmed DLBCL from 2010 to 2019 in a single center. Patients with primary central nervous system DLBCL, primary cutaneous DLBCL, or histological transformation from any low-grade lymphoma were excluded because of their distinct disease characteristics. Diagnosis and classification were performed according to the 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues [13].

Data collection

Clinical data, including demographic information, medical history, laboratory data, pathology reports, imaging studies, age, sex, Ann Arbor stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), and body surface area (BSA) were collected by reviewing the medical records of all participants. Laboratory data included complete blood cell counts and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Bone or bone marrow involvement was determined by pathological review of bone marrow biopsy or positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging. The age-adjusted international prognostic index (aa-IPI) was calculated for the analysis, and the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [14] was used to evaluate the impact of comorbidities on clinical outcomes.

DLBCL treatment

Patients received a combination of rituximab and conventional chemotherapy. The standard R-CHOP regimen included rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 (up to a maximal dose of 2 mg), and prednisolone 40 mg/m2 for 5 days. If anthracycline was not prescribed, etoposide was used as the alternative. Oral cyclophosphamide or etoposide could be substituted depending on the clinician’s choice. Patients were treated every 3 - 4 weeks for six to eight planned treatment courses. To compare the dose intensity between different groups, we utilized the percentile to the regular reference dose (cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2, epirubicin 75 mg/m2, IV etoposide 100 mg/m2, oral etoposide 300 mg) of chemotherapy in each cycle and then divided it by the number of completed cycles to obtain the mean value. The different regimens, doses, and patient numbers were calculated. Prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy was performed if the spinal cord or adrenal glands were involved. Radiotherapy was performed if residual disease was observed after chemotherapy. Considering the advanced age of the patients, autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation was not performed. The therapeutic intervention and choice of regimen for each patient was determined by their physicians and performed after giving full explanation to the patients and their families. Prophylactic strategies for tumor lysis syndrome, such as steroids for cytoreduction, were used in patients with a high tumor burden. If febrile neutropenia (FN) or neutropenia occurred, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was immediately prescribed and prophylactically administered in subsequent courses.

Clinical outcome and toxicity evaluation

Treatment response was categorized as complete remission (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) using the international workshop criteria. The overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the proportion of patients whose best response was either CR or PR. PFS was defined as the duration from the date of diagnosis to the date of tumor progression confirmed by imaging studies, clinical assessments, or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Adverse effects (AEs), such as FN, infection, polyneuropathy (PN), and all grade AEs were recorded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 4.0 (CTCAE 4.0). Hospitalization was defined as admission to the hospital within 30 days after the end of any chemotherapy cycle. Treatment-related mortality (TRM) was defined as death within 14 days from treatment-related grade 3-4 infection, or death from treatment-related cardiovascular events.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of clinical characteristics, AEs, and response rates among different treatment strategies were analyzed using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. The median OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier (KM) method. Prognostic factors associated with survival were evaluated using univariate and multivariate Cox regression models and selected using the forward selection (conditional) method. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and Youden’s index were used to study the association between the response and cut-off values of laboratory data, such as BSA, LDH, and chemotherapy dose percentile. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 26.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical approval

This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital reviewed and approved the process of acquiring data from the participants (IRB No. 202000333B0).

| Results | ▴Top |

A total of 124 patients (≥ 75 years) were diagnosed with DLBCL, of whom 33 (26.6%) only received cytoreduction treatment with steroids or rituximab alone due to poor medical conditions at the time of diagnosis, and data for Ann Arbor stage and aa-IPI score were missing. Another seven patients received both rituximab and steroid for several cycles. All of them were excluded (n = 40).

Patients (n = 84) that received chemotherapy were classified into two regimen combo groups: ACR group and non-ACR group. Patients in ACR group were treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, anthracycline (doxorubicin and epirubicin), vincristine, and prednisolone. Those in the non-ACR group were treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide in oral or intravenous form, vincristine (oncovin), and prednisolone (R-COP) as the backbone, in addition to etoposide in its oral or IV form (R-CVOP) or not. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There was a statistically significant difference in patient age, CCI, ECOG, and BSA, which might be reflected in the physician’s treatment strategies. There were no differences in sex, aa-IPI, Ann Arbor stage, germinal center B cell (GCB), or non-GCB type according to Han’s criteria, LDH, extra-nodal site involvement, and subsequent lines of treatment among groups. There was no significant difference between the comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, history of arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and cerebrovascular events) among the groups.

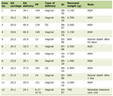

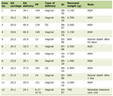

Click to view | Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Total Patients |

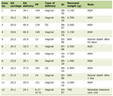

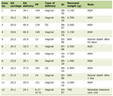

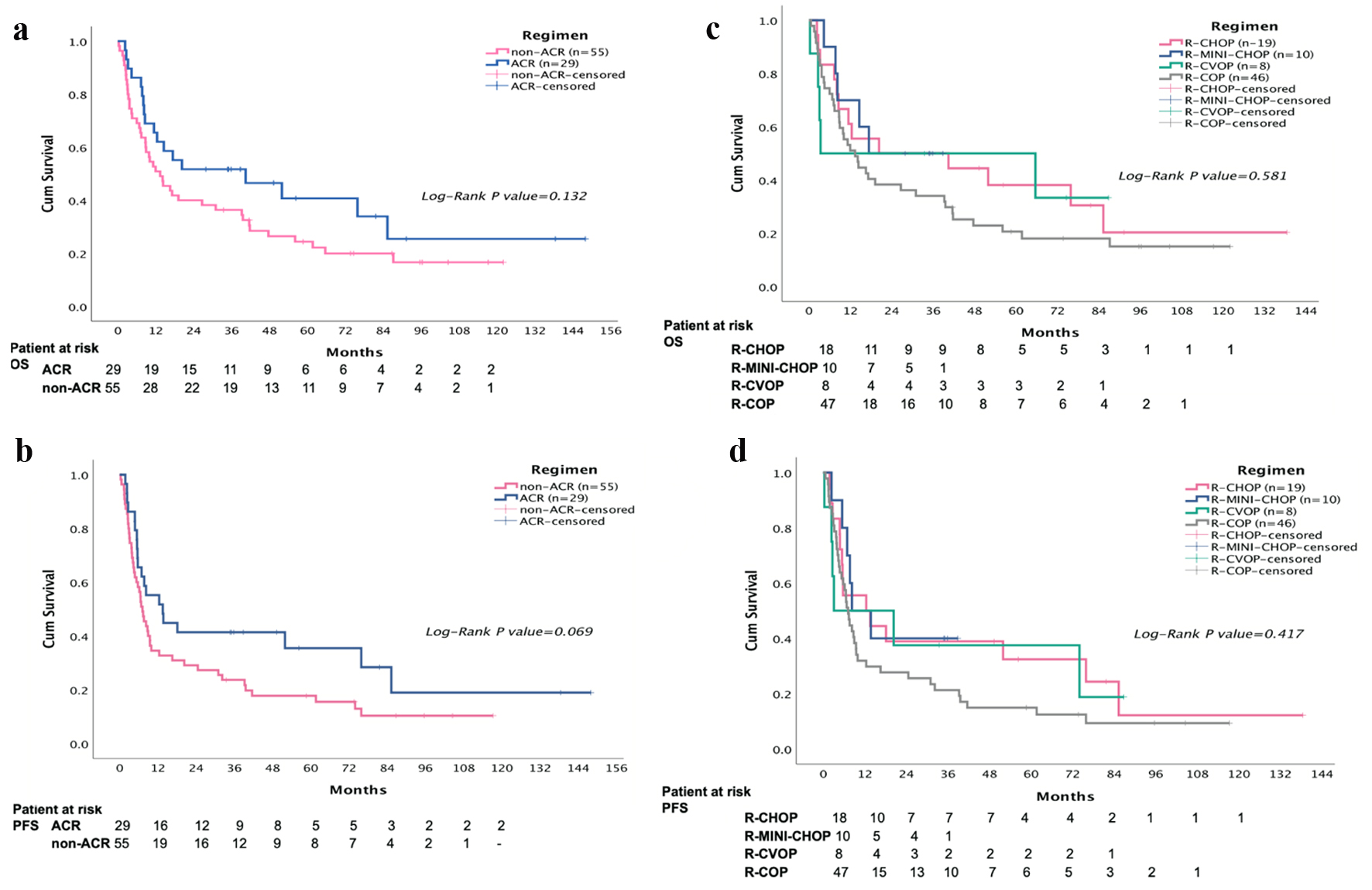

Thirty-eight of the 84 patients (45.2%) completed the treatment course (58.6% and 38.1% in the ACR and non-ACR group, respectively; P = 0.059) (Table 2). The ORR was 77.3% and CR rate was 35.7% (Table 3). The median OS and PFS were 14.6 months (95% CI, 7.0 - 30.0 months) and 7.7 months (95% CI, 5.3 - 10.2 months), respectively (Fig. 1). The mean follow-up time was 33.3 months. The cumulative anthracycline dose in the ACR group was 134 mg/m2 (range, 12 - 279 mg/m2). As shown in Table 4, the mean percentile of the reference chemotherapy dose of cyclophosphamide and vincristine in each cycle showed no significant difference. There was no significant difference in survival improvement between ACR group and non-ACR group (40.4 vs. 13.4 months; P = 0.132) but both ACR and non-ACR groups had better PFS than no-chemotherapy group (n = 40) (1.24 months; P < 0.001). ACR group had higher CR rate than non-ACR group (44.8% vs. 30.9%, P = 0.206). ACR group had more FN episodes (24.1%) than those in the non-ACR group (16.3%) (P = 0.388).

Click to view | Table 2. Chemotherapy-Related AEs |

Click to view | Table 3. Distribution of Response and Adverse Events Between ACR and Non-ACR Groups |

Click for large image | Figure 1. The median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were 14.6 months (95% confidence interval (CI), 7.0 - 30.0 months) and 7.7 months (95% CI, 5.3 - 10.2 months), respectively. The mean follow-up time was 33.3 months. Overall, the 3-year OS in R-CHOP, R-mini-CHOP, R-CVOP, and R-COP is 47.0%, 50%, 50%, and 23%; 3-year PFS is 42%, 40%, 38%, and 15% (P = 0.453 and 0.292; 3-year OS and 3-year PFS). |

Click to view | Table 4. Regimen Combo and Percentile to Regular Reference Dose |

In sub-group analysis, cyclophosphamide and vincristine doses in these groups were not significantly different from others. Ten patients received reduced doses of both anthracycline and cyclophosphamide (≥ 50% reduction) (which is known to be called “R-mini-CHOP”). The sub-analysis showed eight patients receiving etoposide (R-CVOP) had lower BSA and higher CCI than ACR group. Six patients receiving R-CVOP aged > 80 years used etoposide and cyclophosphamide orally, and only two patients aged < 80 years used IV chemotherapy. However, the dose of cyclophosphamide was different (mean ± SE: 76±2% vs. 58±2%; P = 0.003) between R-COPIV (n = 26) and R-COPoral (n = 20). In the ROC analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) of cyclophosphamide for overall response (CR, PR) was only 0.419, indicating that the intensity of cyclophosphamide dose seemed to have less positive association with the overall response. No significant differences in characteristics were found between R-COPIV (n = 26) and R-COPoral (n = 20) (ORR: 80% versus 60%, P = 0.314). Patients with extra-nodal site involvement and women treated with R-COP had shorter PFS (P = 0.20; P = 0.018). Therefore, R-COP should be avoided when treating these patients.

Overall, the 3-year OS in R-CHOP, R-mini-CHOP, R-CVOP, and R-COP respectively is 47.0%, 50%, 50%, and 23%; 3-year PFS is 42%, 40%, 38%, and 15% (P = 0.453 and 0.292; 3-year OS and 3-year PFS) (Fig. 1). The 3-year OS for R-COPIV and R-COPoral is 23% and 20%.

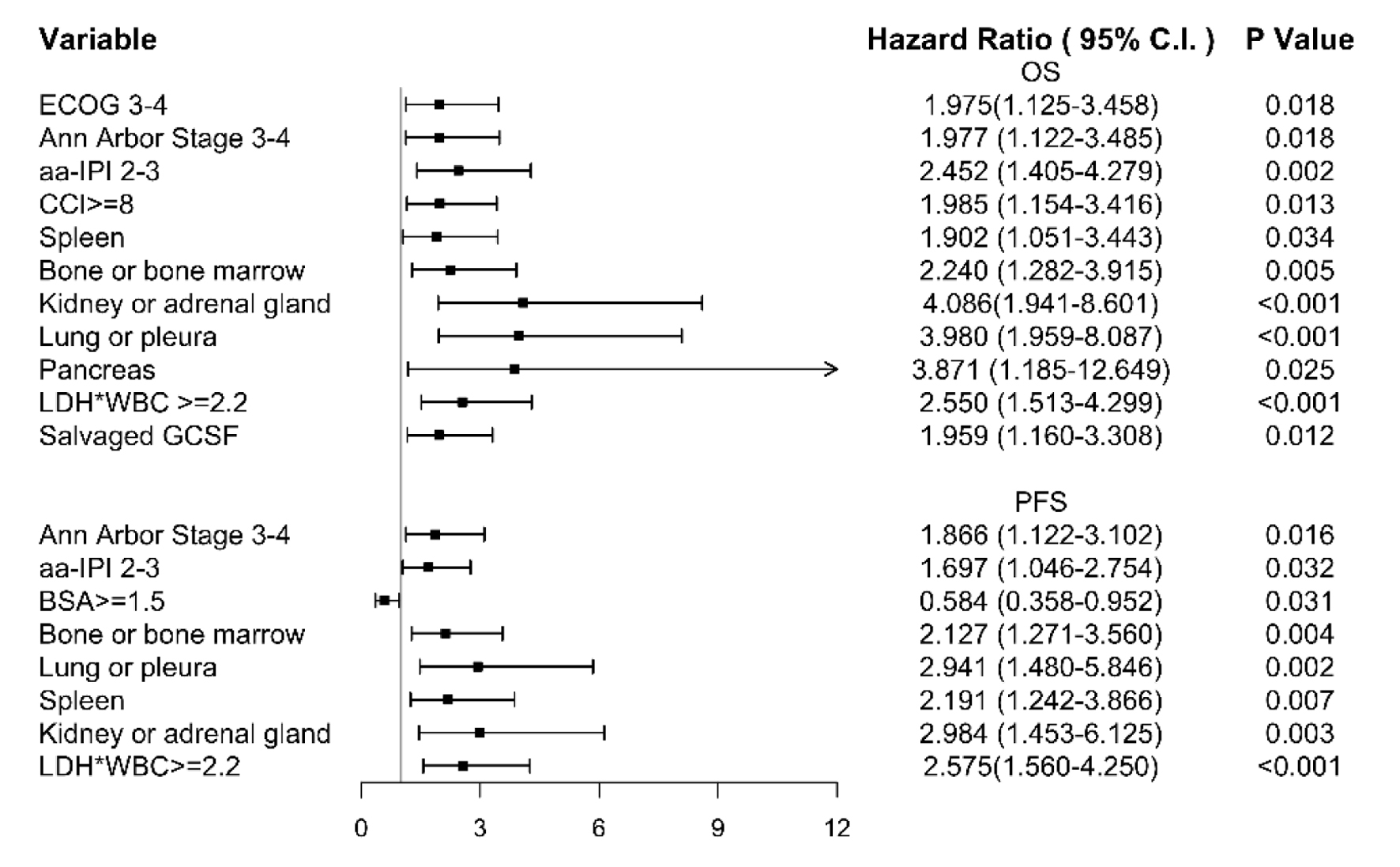

Using Cox regression method, we found age and sex were not prognostic factors for either OS or PFS. Women had shorter PFS although the differences were not statistically significant. A higher LDH level was correlated with a poor response rate (AUC = 0.733), PFS (P = 0.018), and OS (P = 0.015). The cut-off level was 300 when we used the ROC curve for negative prediction of the overall response in our study. White blood cell (WBC) ≥ 10,000/µL was a prognostic factor for both OS and PFS, but only six patients had WBC levels above 10,000 µL. Furthermore, we used the multiplication of both LDH and WBC counts (LDH × WBC × 10-6) for OS and PFS in the Cox regression analysis. LDH × WBC level was strongly correlated with treatment response and the multivariate Cox regression risk factors for OS and PFS. Kidney or adrenal gland involvement is a powerful and independent factor for both OS and PFS prediction. Lung or pleural involvement also harms OS. Other involved sites, such as the bone or bone marrow, kidney or adrenal gland, and spleen are also risk factors for disease progression (Fig. 2). In conclusion, stage, aa-IPI, LDH × WBC level and involved bone or bone marrow, lung or pleura, spleen, and kidney or adrenal glands strongly correlated with worse OS and PFS. Higher BSA had positive effect on PFS, which may indicate more intensive dose could be applied and reflect on the better response. Higher ECOG, CCI, and salvaged GCSF use are also the independent factors for OS.

Click for large image | Figure 2. We used multivariate analysis on overall survival. The stage, age-adjusted international prognostic index (aa-IPI), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) × white blood cell (WBC) level and involved bone or bone marrow, lung or pleura, spleen, and kidney or adrenal glands strongly correlated with worse overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). High body surface area (BSA) had positive effect on PFS. Higher Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), and salvaged granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) use are also the independent factors for OS. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

R-CHOP is the standard treatment for DLBCL and reduced-dose R-CHOP has been proposed in several studies [15-17]. However, in our study, more than a quarter of patients had no chance to receive chemotherapy and died soon (n = 33), with a median OS of 0.89 months. This indicated that these patients were not eligible to receive intensive chemotherapy due to poor comorbidity or aggressive behavior of DLBCL. Our study showed better survival benefit in patients receiving ACR regimen without statistical significance. However, majority of patients in our hospital received minor chemotherapy, such as R-mini-CHOP, R-COP or R-CVOP, with oral form or IV form cyclophosphamide. We found there Is no difference in survival rate and response rate in the oral form or IV form chemotherapy. And higher anthracycline dose does not correlate with higher response rate; nevertheless, the PFS of R-CHOP is better than R-mini-CHOP and R-CVOP without statistical significance, but OS of R-CHOP is not better than the other regimens, and the result is different from the other studies. In a retrospective trial, patients aged > 80 who received ACR regimen (n = 157) had significantly longer failure-free survival (FFS) than those who received non-ACR regimen (n = 20), with 3-year FFS rates of 63-74% and 23% [18]. In another study, etoposide was administered at a dose of 50 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and 100 mg/m2 PO on days 2 and 3 in each cycle. The 5-year thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) was similar in patients treated with R-CVOP compared to that in patients in the R-CHOP control group (57% vs. 62%, respectively, P = 0.21). The 5-year OS was lower in patients receiving R-CVOP than in those in the R-CHOP control group (49% vs. 64%, P = 0.02), which may reflect the underlying comorbidities and frailty in this population [19]. In our study, patients with younger age, lower CCI, better PS, and higher BSA were classified into the ACR group (n = 29). Interestingly, we found higher dose of anthracycline was not associated with better treatment response, which is similar to previous study [20], but the OS in ACR group is better than the non-ACR group without statistical difference. In patients who could not tolerate R-CHOP, R-mini-CHOP, R-CVOP or R-COP would be another choice for patients considering anthracycline cardiotoxicity and chemotherapy-related myelosuppression. In a retrospective study, it was reported that R-COP had 31.9% in 2-year survival rate, and median OS was 12.6 months [21]. In our study, R-COPIV and R-COPoral showed similar ORR and OS. Although the mechanism of orally administered cyclophosphamide is different from that of IV cyclophosphamide, the efficacy and toxicity results seem to be similar in our study.

The choice of regimen and timing of chemotherapy initiation is crucial and difficult, and further trials are needed to identify patients at high or low risk. Recently, the importance of pretreatment strategies before standard chemotherapy has been emphasized in several studies. Five treated patients had delayed initiation of rituximab or chemotherapy (more than 60 days from the day of diagnosis), but each had a good response to steroids and had prolonged survival. In addition, seven patients receiving both rituximab and steroid for several cycles had strikingly longer OS but shorter PFS (63 and 5.4 months), who were significantly older than other patients receiving chemotherapy (71.4% above 85%; P = 0.002), poorer ECOG (P = 0.003) but favorable ORR (85.7%; P = 0.322). However, we could not find any difference between these patients and chemotherapy group toward stage, CCI, involved site, or tumor size, for the limited number of the cases. The result implied these patients using only steroid and rituximab may be fragile or have more comorbidity to receive intensive or myelosuppressive treatment. They tend to receive more subsequent lines of therapy (57.1% received more than one anti-cancer therapy) afterward, which may intimate that better response rate and lower toxicity may translate into better OS in older patients with DLBCL.

Within an elderly cohort in which comorbidity is likely to be high, the CCI will have reduced utility if it cannot distinguish between a score of 2, representing mild to moderate comorbidity, and a score of 8, representing severe comorbidity. Hence, we recommend using the CCI score as a continuous variable [22]. In our study, CCI ≥ 8 and salvaged G-CSF use were strong prognostic factors for OS in the multivariate Cox regression model. BSA ≥ 1.5 m2 had a protective effect on PFS (not shown). A retrospective analysis of 100 patients treated with reduced-dose R-CHOP (50-80%) showed that the relative dose intensity did not affect survival, but a CCI score (summation of comorbidities that categorizes patients into low-intermediate risk for scores 0 - 3 and high-risk for scores higher than 4) higher than 3 was associated with poorer outcomes [23].

There is no standard protocol for choosing the regimen and routine cardiac echo or brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) measurement, neither before nor after anthracycline-based treatment. A prospective trial found that patients with NT-proBNP ≥ 600 pg/mL had a 3.97 times higher risk of cardiotoxicity than those with lower values (P = 0.001). Patients with a FRESCO risk score [24] of 4.5% or higher (body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and smoking) also had a significantly increased risk of cardiotoxicity (HR: 2.54; P = 0.048) [25]. Although we did not adopt these risk scores in our study, it may be a better tool for choosing the initial regimen for older patients with DLBCL.

Limitation

Due to the limitation of incomplete data, we were unable to analyze the characteristics between seven patients using rituximab and steroid only and 33 untreated ones. The patient numbers in R-CVOP (n = 8) are much less than R-CHOP (n = 29) and R-COP (n = 46), thus we classified them into ACR and non-ACR groups. But there is different response rate and survival between R-CVOP and R-COP. The classification of GCB or non-GCB is not completed, and the biopsy tissue is reviewed by different pathologists. There are no standard protocols for choosing the regimen in these very elderly patients, and routinely cardiac echo or BNP before or after anthracycline-based treatment is not performed.

Conclusion

Although R-CHOP is still the standard treatment for patients with DLBCL, older patients may not be able to tolerate the regimen well. Patient’s age, CCI, ECOG, and BSA, which might be reflected in the physician’s treatment strategies and may turn into the result of survival. In our study, the toxicity, efficacy, and KM curve for OS and PFS in the non-ACR group were lower than those in the ACR group, without statistical significance. R-CVOP (n = 8) had similar OS with R-mini-CHOP (n = 10) in our study. The result does not mean etoposide could totally substitute for anthracycline, but etoposide did have lower early progression rate (12.5%), and it may be an option for frail patients with comorbidity. Oral form cyclophosphamide and etoposide could be considered as a substitute for IV administration because of the similar effect and toxic profile.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This study did not receive any funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Pi-Han Liao, Ching-Yuan Kuo, Ming-Chun Ma, Chin-Kai Liao, Sung-Nan Pei, and Ming-Chung Wang have participated in take care of the patients; Pi-Han Liao is the first author to write the whole article; Ming-Chung Wang is the corresponding author for approval of the final version.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; ORR: overall response rate; CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; G-CSF: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

| References | ▴Top |

- Chuang SS, Chen SW, Chang ST, Kuo YT. Lymphoma in Taiwan: Review of 1347 neoplasms from a single institution according to the 2016 Revision of the World Health Organization Classification. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116(8):620-625.

doi pubmed - Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

doi pubmed - Fisher RI, Miller TP, O'Connor OA. Diffuse aggressive lymphoma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2004;2004(1):221-236.

doi pubmed - Nabhan C, Smith SM, Helenowski I, Ramsdale E, Parsons B, Karmali R, Feliciano J, et al. Analysis of very elderly (>/=80 years) non-hodgkin lymphoma: impact of functional status and co-morbidities on outcome. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(2):196-204.

doi pubmed - Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Myers A, Kim G, Pazdur R. FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: A 10-year experience by the U.S. food and drug administration. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15 suppl):10009.

doi - Weisenburger DD. Epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: recent findings regarding an emerging epidemic. Ann Oncol. 1994;116(Suppl 1):19-24.

doi pubmed - Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235-242.

doi pubmed - Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Klasa R, MacPherson N, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5027-5033.

doi pubmed - Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010;116(12):2040-2045.

doi pubmed - Kumar A, Fraz MA, Usman M, Malik SU, Ijaz A, Durer C, Durer S, et al. Treating diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the very old or frail patients. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19(10):50.

doi pubmed - Khan Y, Brem EA. Considerations for the treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the elderly. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2019;14(4):228-238.

doi pubmed - Cheng CL, Liu JH, Chou SC, Yao M, Tang JL, Tien HF. Retrospective analysis of frontline treatment efficacy in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(1):28-37.

doi pubmed - Swerdlow SH. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. WHO Classification of Tumours. 2008;22008:439.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

doi - Peyrade F, Jardin F, Thieblemont C, Thyss A, Emile JF, Castaigne S, Coiffier B, et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):460-468.

doi - Aoki K, Takahashi T, Tabata S, Kurata M, Matsushita A, Nagai K, Ishikawa T. Efficacy and tolerability of reduced-dose 21-day cycle rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone therapy for elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(11):2441-2447.

doi pubmed - Merli F, Luminari S, Rossi G, Mammi C, Marcheselli L, Tucci A, Ilariucci F, et al. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and rituximab versus epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, prednisone and rituximab for the initial treatment of elderly "fit" patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the ANZINTER3 trial of the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(4):581-588.

doi pubmed - Chihara D, Westin JR, Oki Y, Ahmed MA, Do B, Fayad LE, Hagemeister FB, et al. Management strategies and outcomes for very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3145-3151.

doi pubmed - Moccia AA, Schaff K, Hoskins P, Klasa R, Savage KJ, Shenkier T, Gascoyne RD, et al. R-CHOP with etoposide substituted for doxorubicin (R-CEOP): excellent outcome in diffuse large B cell lymphoma for patients with a contraindication to anthracyclines. Blood. 2009;114:408.

doi - Xu PP, Fu D, Li JY, Hu JD, Wang X, Zhou JF, Yu H, et al. Anthracycline dose optimisation in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(6):e328-e337.

doi - Laribi K, Denizon N, Bolle D, Truong C, Besancon A, Sandrini J, Anghel A, et al. R-CVP regimen is active in frail elderly patients aged 80 or over with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(10):1705-1714.

doi pubmed - Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, Jani AB, Vijayakumar S. An electronic application for rapidly calculating Charlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:94.

doi pubmed - Ono K, Tsujimura H, Maruyama S, Satou A, Sugawara T, Kumagai K. Factors relating to the favorable outcome in reduced-dose R-CHOP therapy for elderly DLBCL Patients. Blood. 2018;132:4241.

doi - Marrugat J, Subirana I, Ramos R, Vila J, Marin-Ibanez A, Guembe MJ, Rigo F, et al. Derivation and validation of a set of 10-year cardiovascular risk predictive functions in Spain: the FRESCO Study. Prev Med. 2014;61:66-74.

doi pubmed - Ferraro MP, Gimeno-Vazquez E, Subirana I, Gomez M, Diaz J, Sanchez-Gonzalez B, Garcia-Pallarols F, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: NT-proBNP and cardiovascular score for risk stratification. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102(6):509-515.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.