| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Original Article

Volume 4, Number 4, December 2015, pages 223-227

Monitoring of Thromboembolic Events Prophylaxis: Where Do We Stand?

Laleh Mahmoudia, Soha Namazia, Shiva Nematia, Ramin Niknamb, c

aDepartment of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

bGastroenterohepatology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

cCorresponding Author: Ramin Niknam, Gastroenterohepatology Research Center (GEHRC), Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Namazi Hospital, Shiraz, Iran

Manuscript accepted for publication October 22, 2015

Short title: Thromboembolic Events Prophylaxis

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jh232e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Thromboembolic events are one of the most important causes of mortality in the hospitalized patients. Evaluation of anticoagulants intake patterns compared to the standard treatment guidelines is necessary for improving the quality of prophylaxis managements. The present study was performed to evaluate the pattern of heparin and enoxaparin intake compared to the standard treatment guidelines for thromboprophylaxis.

Methods: The present study was conducted on 305 patients admitted to the two referral teaching hospitals. The patients were classified according to the treatment guidelines of American College of Chest Physicians and based on the type of risk (low, moderate, and high). Finally, prophylaxis regimen was assessed based on the standard treatment guidelines and the intervention was performed in case of contradiction.

Results: In this study, averagely, prophylactic regimen showed 83.3% compliance with the standard treatment guidelines. Moreover, 188 patients (61.6%) were in moderate and high risk groups and needed prophylaxis therapy. Among these patients, 93% (175 patients) received appropriate prophylaxis. According to the results, being above 40 years old, infection, and inactivity were the most important risk factors in the patients with the prevalence of 81.6%, 47.9%, and 43.3%, respectively.

Conclusion: Although treatment guidelines are available for the prophylaxis of thromboembolic events, prophylaxis regimens are not always administered in accordance with these guidelines. Failure to observe these guidelines could increase the cost of treatment and risk of thrombosis as well as other serious problems for the patients.

Keywords: Anticoagulation protocol; Heparin; Enoxaparin; Prophylaxis; Guideline

| Introduction | ▴Top |

A venous thromboembolic event (VTE) is considered as an important cause of preventable disability and mortality [1-5]. VTE attacks in hospitalized patients are associated with high rates of mortality. The patients admitted to ICU are particularly exposed to developing VTE and it can increase the risk of mortality in this population [6]. However, the real incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates of the VTE are likely to be underestimated because of its clinically silent nature [7].

Several clinical trials and meta-analyses have shown the efficacy and safety of prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of VTE. In addition, Consensus Conferences and Guidelines for VTE prophylaxis have been published recommending the use of prophylactic unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) such as enoxaparin in the patients who are at risk of VTE [8-10]. According to these guidelines, the use of anticoagulants can reduce the adverse events of VTE as well as the healthcare costs [3-5]. In spite of this scientific evidence, several studies [6, 10-14] have shown low efficiency and improper use of prophylaxis. Up to now, a few studies such as the study by Khalili et al [4] have been conducted to compare the compatibility of the prophylaxis methods for VTE with the standard treatment guidelines in Iran. Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the compatibility of the prophylaxis methods for VTE used at two referral teaching hospitals of Shiraz, Iran with the standard guides of prophylaxis.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This was a prospective cross-sectional study being conducted in Namazi and Shahid Faghihi hospitals, both teaching tertiary healthcare canters affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences during a 7-month period from September 2012 to March 2013. These two hospitals are the largest referral hospitals in the Southern of Iran. Three hundred and five patients out of the 460 patients admitted to the wards of internal, surgical, and cardiac care were selected for inclusion in the study. Patients with limited bedridden duration (less than 24 h), had received therapeutic doses of heparin or enoxaparin, and had incomplete information, were excluded from the study. The study protocol was approved by institutional review board of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. As this was a prospective study, no informed written consents were required.

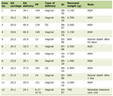

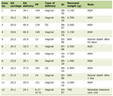

The patients were evaluated regarding age, gender, body mass index, the type of risk factors for VTE, history of diseases such as VTE, heart failure, and known thrombophilia, laboratory test results including complete blood count (CBC), Scr, Clcr (calculated according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula [15]), prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalized ratio (INR), and contraindications for administration of heparin/enoxaparin. The physicians’ demographic information including field of specialization, scientific degree, and gender were recorded, as well. Furthermore, information on drugs and regimens for VTE prophylaxis during hospitalization were recorded for all the patients. Then, the patients were classified according to the treatment guidelines of American College of Chest Physicians 2008 (ACCP) [16] and based on the type of risk (low, moderate, and high) (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Categories of Risk Groups for Venous Thromboembolism in Inpatients |

In this study, no follow-ups were performed for patients. Finally, prophylaxis regimen was assessed based on the treatment guidelines of ACCP. The interventions were performed in case of contradiction. The following indicators of adherence to guideline recommendations were analyzed: 1) the proportion of patients receiving appropriate prophylaxis according to patients’ risk category (low-, moderate- and high-risk patients); 2) the proportion of appropriate types of prophylaxis in moderate- and high-risk patients; 3) the proportion of appropriate dosage of heparin and enoxaparin in patients; and 4) the rate of heparin and enoxaparin prophylaxis compliance. Finally, the data were evaluated for the influence of physicians’ gender and academic degree (assistant professor, associated professor and professor) on the rate of appropriate prophylaxis.

All the statistical analyses were performed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 17.0. Parametric variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD, while non-parametric ones were expressed as percentage. The data were compared between subgroups using one-way ANOVA, and post hoc Tukey, Kruskal-Wallis, and Chi-square tests were appropriate. A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

In this study, the participants’ age ranged from 20 to 91 years (mean ± SD: 59.3 ± 19.2). The study included a total of 305 patients: 217 in the internal medicine, 69 in the surgical, and 19 in the cardiac care wards.

In this study, 219 (71.8%) out of the 305 patients received prophylaxis regimen. Among the 305 patients, 175 (57.4%) received appropriate prophylaxis. Prophylaxis was prescribed for eight patients (2.5%) who met the disagreement guidelines for the use of antithrombotic therapy. Out of these patients, four (1.25%) had contraindications for receiving prophylaxis and four (1.25%) had used the wrong type of anticoagulant (heparin was used instead of enoxaparin). On the other hand, 38 patients (12.4%) did not need the prophylaxis, but received the prophylaxis treatments. Among the 219 patients who received prophylaxis, 196 (89.5%) and 23 (10.5%) patients received heparin and enoxaparin, respectively. Furthermore, prophylaxis with heparin and enoxaparin was respectively performed by 77% and 95.7% compliance with the ACCP guidelines (Table 1). Prophylactic regimen showed 83.3% compliance with the standard treatment guidelines in the three wards. No significant differences were observed among the three departments regarding the rate of this compliance (P = 0.98).

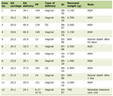

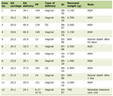

Based on the treatment guidelines of ACCP, 117 (38.3%), 171 (56.0%), and 17 patients (57.5%) were in low-risk, moderate-risk, and high-risk groups, respectively (Table 2). Moreover, 188 patients (61.6%) were in moderate- and high-risk groups and needed prophylaxis regimen. Among these patients, 175 (93%) received appropriate prophylaxis. The age of above 40 years old, infection, and physical inactivity were the most important risk factors in the patients with the prevalence of 81.6%, 47.9%, and 43.3%, respectively (Table 3). The results regarding the prophylaxis according to number of risk factors of patients are reported in Table 4. The rate of receiving prophylactic regimen was higher in the patients with more risk factors (P = 0.001). In patients with three or more number of the risk factors, the probability of prophylaxis was 50-92%. The present study findings revealed no significant differences between the physicians’ gender (P = 0.084) and academic degree (P = 0.119) and the rate of prophylaxis compliance with the standard treatment guidelines.

Click to view | Table 2. Risk Factors of Patients and Prophylaxis According to Risk Categories in Guidelines |

Click to view | Table 3. Identified Risk Factors for VTE in Patients Enrolled in the Study |

Click to view | Table 4. Prophylaxis According to Number of Risk Factors of Patients |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Although the evidences have shown high effectiveness of prophylaxis against VTE, using proper doses of anticoagulants and comprehensive coverage of the patients have revealed various degrees of inconsistency with the standard guidelines for thromboprophylaxis. Appropriate prophylaxis management can reduce the cost of treatment, duration of hospital stay, and the rate of side effects [6, 10]. Despite the existence of many different guidelines, adequate thromboprophylaxis is not being correctly prescribed: high-risk patients are under-treated and low-risk patients are over-treated [17].

According to the guidelines published by ACCP (8th Edition), UFH or LMWH is recommended to be used for thromboprophylaxis in the patients with moderate to high risk for VTE [16].

In several studies, prophylactic therapy showed 13-79% compliance with the standard treatment guidelines [1, 4, 10, 12, 17, 18]. The results of the present study showed 83.3% compliance with ACCP guidelines. High levels of agreement with the guidelines in some studies may be due to the investigation of the patients with high risk of VTE, such as the patients hospitalized in surgical and intensive care units [10, 17-20]. For example in the study by Vallano et al [10], the rates of prophylaxis compliance with the standard treatment guidelines were 85.2% at at surgery, 90.9% at ICU, 62.5% at emergency, and 69.9% at general wards. Nevertheless, in the present study, no significant difference was observed among the three wards regarding the rate of compliance. This consistency in the two educational hospitals might be related to the integrated management by SUMS and the fact that the same physicians worked in the both hospitals.

Studies investigated quality of VTE prophylaxis in the patient with different risk of VTE has produced varied results. Zeitoun et al [21] concluded that patients with moderate risk of VTE were more likely to receive inappropriate prophylaxis than patients with low and high risk of VTE. Deheinzelin et al [17] found that with high risk and moderate risk patients were more likely to receive inappropriate prophylaxis than patients with low risk of VTE. Some studies have pointed out under utilization of prophylaxis in high-risk patients [7, 14]. In our study, 95.9% of the patients with moderate and 100% of those with high risk VTE received prophylaxis. The findings of our study and other similar studies [10, 12] showed that the patients with moderate and high risk of VTE received acceptable levels of appropriate prophylaxis treatments.

In the current study, the most common risk factors of VTE were age above 40 years (81.6%), infection (47.9%), physical inactivity (43.3%), respiratory problems (28.5%), and surgery (27.2%). These results were in agreement with those of the study conducted by Vallano et al [10] that reported the most common risk factors to be age above 40 years (84%), surgery (37%), physical inactivity (36.5%), and malignancy (32%). In another study by Bratzler et al [12], malignancy with the prevalence of 55% was reported as the greatest risk factor for VTE.

Our study results showed that the patients with more risk factors were more likely to receive prophylaxis. Based on the findings of Vallano et al [10] average number of risk factors was higher in the patients with high risk of VTE. Thus, paying attention to the type and frequency of risk factors is important for performing appropriate prophylaxis.

In this study, among the nine patients with active gastric ulcer and severe thrombocytopenia who were contraindicated for prophylaxis, four patients received heparin. In a similar study by Khalili et al [4], two contraindicated patients with severe thrombocytopenia received heparin. Contraindications to the use of anticoagulant medication can cause increase in the risk of complications, such as bleeding or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. These side effects can lead to serious health problems in the patients [22]. Therefore, isolation and identification of these patients is necessary before prophylaxis regimen.

The results of the present study showed that the physicians’ gender (P = 0.084) and academic degree (P = 0.119) had no significant effect on prophylaxis compliance with the standard treatment guidelines. Which might be related to the use of standard guidelines by physicians could reduce the individual mistakes. Nevertheless, some studies concluded that difficulties in using the guidelines and cumbersomeness are frequently quoted as reasons to avoid the correct use of the thromboprophylaxis guidelines [17, 22, 23].

One of the limitations of the present study was that the patients were followed up and evaluated for a short period of time. Another limitation was that the study was conducted in two educational hospitals. It was better to compare the educational hospitals to private ones. Moreover, the target population of this study included the physicians with academic degrees. However, the physicians in smaller towns may have different levels of knowledge, attitudes, and practices in this area. Hence, the results cannot be generalized to other hospitals and medical centers.

Although treatment guidelines are available for the prophylaxis of thromboembolic events, prophylaxis treatments are not always administered in accordance with these guidelines. Appropriate prophylaxis management can reduce the cost of treatment, duration of hospital stay, and mortality rate as well as other serious problems for the patients. Thus, training and development of local treatment guidelines and monitoring the proper implementation of these guidelines can reduce the unintended mistakes for prescribing prophylaxis.

Conflict of Interest

There is not any conflict of interest to be declared regarding the manuscript.

| References | ▴Top |

- Byrne S, Weaver DT. Review of thromboembolic prophylaxis in patients attending Cork University Hospital. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(3):439-446.

doi pubmed - Carson W, Schilling B, Simons WR, Parks C, Choe Y, Faria C, Powers A. Comparative effectiveness of dalteparin and enoxaparin in a hospital setting. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25(2):180-189.

doi pubmed - Dentali F, Douketis JD, Gianni M, Lim W, Crowther MA. Meta-analysis: anticoagulant prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(4):278-288.

doi pubmed - Khalili H, Dashti-Khavidaki S, Talasaz AH, Najmedin F, Hosseinpoor R. Anticoagulant utilization evaluation in a teaching hospital: a prospective study. J Pharm Pract. 2010;23(6):579-584.

doi pubmed - Mismetti P, Laporte-Simitsidis S, Tardy B, Cucherat M, Buchmuller A, Juillard-Delsart D, Decousus H. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in internal medicine with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparins: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83(1):14-19.

pubmed - Todi S, Sinha S, Chakraborty A, Sarkar A, Gupta S, Das T, et al. Utilisation of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in medical/surgical intensive care units. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 2003;7(2):103.

- Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Patwardhan NA, Jovanovic B, Forcier A, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(5):933-938.

doi pubmed - Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, Colwell CW. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S-453S.

- Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, Pineo GF, Colwell CW, Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S-175S.

doi pubmed - Vallano A, Arnau JM, Miralda GP, Perez-Bartoli J. Use of venous thromboprophylaxis and adherence to guideline recommendations: a cross-sectional study. Thromb J. 2004;2(1):3.

doi pubmed - Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Forcier A, Patwardhan NA. Physician practices in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(8):591-595.

doi pubmed - Bratzler DW, Raskob GE, Murray CK, Bumpus LJ, Piatt DS. Underuse of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for general surgery patients: physician practices in the community hospital setting. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(17):1909-1912.

doi pubmed - Keane MG, Ingenito EP, Goldhaber SZ. Utilization of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the medical intensive care unit. Chest. 1994;106(1):13-14.

doi pubmed - Valles JA, Vallano A, Torres F, Arnau JM, Laporte JR. Multicentre hospital drug utilization study on the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. The Venous Thromboembolism Study Group of the Spanish Society of Clinical Pharmacology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;37(3):255-259.

doi pubmed - Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31-41.

doi - Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schunemann HJ, American College of Chest P. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):110S-112S.

- Deheinzelin D, Braga AL, Martins LC, Martins MA, Hernandez A, Yoshida WB, Maffei F, et al. Incorrect use of thromboprophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in medical and surgical patients: results of a multicentric, observational and cross-sectional study in Brazil. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(6):1266-1270.

doi pubmed - Yu HT, Dylan ML, Lin J, Dubois RW. Hospitals' compliance with prophylaxis guidelines for venous thromboembolism. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(1):69-76.

doi pubmed - Amin A, Spyropoulos AC, Dobesh P, Shorr A, Hussein M, Mozaffari E, Benner JS. Are hospitals delivering appropriate VTE prevention? The venous thromboembolism study to assess the rate of thromboprophylaxis (VTE start). J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;29(3):326-339.

doi pubmed - Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, Goldhaber SZ, Kakkar AK, Deslandes B, Huang W, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):387-394.

doi - Zeitoun AA, Dimassi HI, El Kary DY, Akel MG. An evaluation of practice pattern for venous thromboembolism prevention in Lebanese hospitals. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;28(2):192-199.

doi pubmed - Kakkar AK, Davidson BL, Haas SK. Compliance with recommended prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism: improving the use and rate of uptake of clinical practice guidelines. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(2):221-227.

doi pubmed - Casey DE, Jr. Why don't physicians (and patients) consistently follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1581-1583.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.