| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Original Article

Volume 1, Number 1, February 2012, pages 15-19

Platelet Activation in Stored Platelet Concentrates: Comparison of Two Methods Preparation

Soleimany Ferizhandy Ali

Iranian blood transfusion organization research center, Tehran, hemmat Exp way, P.O.Box: 14665-1157, Tehran, Iran

Manuscript accepted for publication January 11, 2012

Short title: Platelet Activation

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jh103e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: This study has determined in vitro quality of 5 days stored platelet concentrates prepared by two different methods. Preparation conditions of platelet may cause platelet activation, which contributes to decreased ability of stored platelet to function. The quality platelets concentrate plays an important role in transfusion therapy. Their quality was assessed using the following parameters: platelets, leukocytes and erythrocytes counts, pH, P-selcetin (CD62P) and Annexin V. P-selectin and Annexin V can be detected on the activated platelet. Annexin V was used as a parameter for quality monitoring of platelet concentrates during storage. The present paper compares quality properties of both platelet preparations in vitro.

Methods: In this experimental study, 30 platelet concentrates prepared with platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates and 30 units via buffy coat-derived platelet concentrate methods. The percentages of Annexin V, P-selcetin expression, platelet, leukocytes and erythrocytes counts and pH were evaluated.

Results: During storage for up to 5 days, buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates units displayed, no significant pH, difference in comparison with platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates preparation (P > 0.05). The mean leukocytes count buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates and platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates was comparable and statistically significant difference was observed (P < 0.05). During storage for up to 5days platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates units displayed significant an increase in the CD62P, Annexin V expressions, as compared with buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates preparation on day 5 (P < 0.05).

Conclusions: The kinetics of CD62P and annexin V levels are influenced by the method used to prepare platelets for storage. The different levels of CD62P and annexin V in buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates and platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates clearly demonstrating a progressive activation process of platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates exceeds that of buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates.

Keywords: P-selectin; Annexin V; Buffy coat

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Preparation conditions and storage of platelet for transfusion may cause platelet activation, which contributes to decreased ability of stored platelet to function and to survive in vivo after transfusion compared with that seen with freshly prepared platelets [1-4].

Platelet transfusion therapy has played an important role in the management of patients [2, 4].

Today, platelet concentrates are routinely manufactured from whole blood by differential centrifugation buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates (BC) or by platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates (PRP-PC) and plateletpheresis [5-7].

Whereas in 1970 and 1985, the use of BC exceeded that of PRP-PC by far. We here report on the difference between both platelet concentrates in functional properties of platelet in BC and PRP-PC is compared over storage of 5 days. Processing and storage may affect both platelet morphology and function and they may thus be less effective when transfused than fresh platelets [1, 3-4, 8-9].

There are several methods for quality control of platelet components including cell counting, pH, swirling and markers for platelet activation [8, 10-11].

Redistribution of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the inner membrane surface to the exterior surface accompanies during platelet activation [11, 12, 13].

The exposure of PS can be measured by using flow cytometry and fluorescent-labeled annexin V. Annexin V was used as a parameter for quality monitoring of platelet concentrates during storage. This essay is based on the principle that annexin V binds to PS, with high affinity and high specificity [8, 12-14].

Activation of thrombocytes is followed by an increased CD62P expression; this protein is the main component of the alpha granules secreted from the granules during storage [7-8].

The aim of this study is to characterize the quality of the changes occurred in the platelet activation parameters during the storage of platelet concentrates derived from BCs and PRP-PCs.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Platelet preparation

Preparation of buffy coat - platelet concentrate (BC)

Thirty whole blood was collected in a 450-ml quadruple bag containing 63 ml of CPDA1 anticoagulant (TERUMO PENPOL, Ltd., Puliyarakonam, Trivandrum, India). The whole blood was first subjected to "hard spin" centrifugation at 3840 rpm for 6 minutes at 22 °C with acceleration and deceleration curves of 7 and 3 respectively. Whole blood was separated into different components according to their specific gravity. After centrifugation the supernatant plasma and the subnanat red cells were transferred into attached satellite containers. Platelet poor supernatant was expressed into one satellite bag and buffy coat into another satellite bag. About 20 - 30 ml of plasma was returned to buffy coat with the aim of cleaning the tubing from residual cells and obtaining an appropriate amount of plasma in the BC. The buffy coat was gently mixed with the plasma and again subjected to 'light spin" centrifugation at 1,200 rpm for 6 minutes at 22 °C, with acceleration and deceleration curves of 5 and 4 respectively, along with one empty satellite bag. The supernatant, platelet rich plasma was expressed into empty platelet storage bag and then tubing was sealed.

Preparation of platelet rich plasma- platelet concentrates (PRP-PC)

Four hundred and fifty ml of whole blood was collected in a 450-ml triple bag containing CPDA1 anticoagulant (TERUMO PENPOL, Ltd. Puliyarakonam, Trivandrum, India), and PRP-PCs was prepared within 4 hours of collection stored for 5 days at 20 - 24°C under constant agitation (n = 30).

Laboratory analysis

On days 0, 1, 3, 5 samples from PRP-PC and BC were taken for analysis under sterile condition.

Manual cell counts were therefore carried out utilizing the improved Neubauer chamber for counting leukocytes (WBC), erythrocytes (RBC) and platelets. The pH was evaluated at the end of the maximum day of storage.

The volume was determined by subtracting the weight of the empty bag from that of full bag. To convert weight to volume, the resultant weight was divided by specific gravity.

Using flow cytomerty, we investigated platelet membrane binding of Annexin V and CD62P expression in platelet stored for up to 5 days under standard blood banking conditions. Special monoclonal antibodies that conjugated with fluorescence dye in flow cytometric method was used for its. Flow cytometry was then performed with side-scater and CD61 gates set to include only individual platelets. A minimum of 5000 events was collected.

Subjects studied

Whereas several studies have been performed concerning the functional and quality properties of BCs and PRP-PCs (M.Bock et al.; 2002; Dijkstra-Tiekstra et al; 2004; Fijnheer R, Pieters RNI; 1990) [6, 8]. Heaton Wal et al compared components prepared by the PRP-PC and BC methods [4]. The results of Fijnheer et al [5]; were also similar and reported WBC contamination/unit in PRP-PC and BC. The results of both the above studies had similar results regarding WBC count/unit as compared to present study, thus highlighting the advantage of BC when compared to PRP-PC as regards to leukocyte contamination.

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. We performed statistical comparison by using 't'-test. A probability of P < 0.05 (two-sided) was used to reject null hypothesis.

| Results | ▴Top |

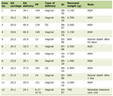

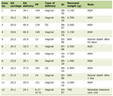

In this experimental study, quality of the platelet concentrates was assessed by cell counts/bag, pH, CD62Pand Annexin V. In the present study, the mean platelet count of BCs and PRP-PCs was 5.9 ± 1.8 × 1010 /unit and 5.6 ± 2.1 ×1010/unit. The mean RBC contamination in BCs and PRP-PCs was 25 ± 2.1 × 108/ unit and 27 ± 2.1 × 108/unit. The mean platelet and RBC counts BCs and PRP-PCs were comparable and statistically no significant difference was observed (P > 0.05). The mean WBC count in PRP-PC and BC units was 43 ± 0.48 ×106/unit, 24 ± 0.39 × 106/unit. The mean leukocyte counts BCs and PRP-PCs were comparable and statistically significant difference was observed (P < 0.05). Buffy coat product showed better leucoreduction than PRP-PCs product. Their mean pH was 6.8 ± 0.1 (mean ± SD) and ranged from 6.6 - 7.01 and no difference was observed between all two types of platelet concentrate. The results of pH and cell counts are listed in Table 1. The volume of individual units was calculated. The mean volume of the PRP-PCs and BCs was 50.6 ± 15.3 ml and 70 ± 20.6 ml. The mean levels CD62P and percentage of Annexin V was comparable and statistically no significant difference was observed on days (0, 1), but there was statistically relevant increase in CD62P and Annexin V on days 3and 5. During storage for up to 5 days PRP-PCs units displayed a significant increase in the CD62P, Annexin V expressions, as compared with BCs units (P < 0.05). The platelet activation markers CD62P and Annexin V are presented in Table 2.

Click to view | Table 1. Cell Counts and pH in Buffy Coat-Derived Platelet Concentrate (BC) and Platelet Rich Plasma-Platelet Concentrates (PRP-PC) |

Click to view | Table 2. Platelet Activation Markers are Stored in Buffy Coat-Derived Platelet Concentrate (BC) and Platelet Rich Plasma-Platelet Concentrates (PRP-PC) |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study has determined in vitro quality of 5 days stored platelet concentrates prepared by two different methods [15]. The detection of platelet activation has been used as a guide to the assessment of the suitability of techniques or conditions under which platelets have been prepared for transfusion. The present paper describes an in vitro comparison of both preparations. The studies suggested that the degree of in vitro activation as evidenced by the expression of CD62P and Annexin V binding were dependent on the different preparative methods [4, 9, 16, 17]. We found that the extent of activation was significantly higher in PRP-PCs than in BCs. It was concluded that, immediately after preparation, PRP-derived platelets are more activated than BC-derived platelets. This is most likely a result of the pelleting that follows the second high-speed centrifugation of the PRP.

The results show that Annexin V binding and CD62P increase after preparation of platelet concentrates from PRP-PCs and BC, and rises progressively during storage under blood bank conditions. Although in both preparations, platelet activation is increased by storage time, BCs are characterized by a much better in vitro than PRP-PCs [3-5, 7]. However, the different CD62P and Annexin V in PRP-PCs and BCs clearly demonstrate that process of activation exceeds that of BCs.Platelets processed by the buffy coat technique showed less p-selectin (CD62P) expression than platelets prepared by the PRP method. This study shows that in addition to pH and cell counts; in vitro platelet activation markers were used to monitor platelet quality [11, 18]. These data suggest that measurement of CD62P and Annexin V may be more desirable markers for clinical studies of activated platelets, since it may be less susceptible to artifactual elevation due to minor variations in sample handling and assay procedures [13-15].

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Tehran blood service for providing platelet concentrates for this project. This project supported by Iranian blood transfusion organization-research center.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rinder HM, Murphy M, Mitchell JG, Stocks J, Ault KA, Hillman RS. Progressive platelet activation with storage: evidence for shortened survival of activated platelets after transfusion. Transfusion. 1991;31(5):409-414.

pubmed doi - Snyder EL, Hezzey A, Katz AJ, Bock J. Occurrence of the release reaction during preparation and storage of platelet concentrates. Vox Sang. 1981;41(3):172-177.

pubmed doi - Herny M, Rinder A, Kenherth A, et al. Platelet activation and its detection during the preparation of platelet for transfusion. Transfusion Medicine reviews 1998; 2:271-2880.

- Heaton WA, Rebulla P, Pappalettera M, Dzik WH. A comparative analysis of different methods for routine blood component preparation. Transfus Med Rev. 1997;11(2):116-129.

pubmed doi - Fijnheer R, Pietersz RN, de Korte D, Gouwerok CW, Dekker WJ, Reesink HW, Roos D. Platelet activation during preparation of platelet concentrates: a comparison of the platelet-rich plasma and the buffy coat methods. Transfusion. 1990;30(7):634-638.

pubmed doi - Bock M, Rahrig S, Kunz D, Lutze G, Heim MU. Platelet concentrates derived from buffy coat and apheresis: biochemical and functional differences. Transfus Med. 2002;12(5):317-324.

pubmed doi - Jerad S, Prane K. The Platelet Storage lesions. Transfusion Medicine Reviews 1997; 2:130-144.

- Dijkstra-Tiekstra MJ, Pietersz RN, Huijgens PC. Correlation between the extent of platelet activation in platelet concentrates and in vitro and in vivo parameters. Vox Sang. 2004;87(4):257-263.

pubmed doi - Matsubayashi H, Weidner J, Miraglia CC, McIntyre JA. Platelet membrane early activation markers during prolonged storage. Thromb Res. 1999;93(4):151-160.

pubmed doi - Kamath S, Blann AD, Lip GY. Platelet activation: assessment and quantification. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(17):1561-1571.

pubmed doi - Albanyan AM, Murphy MF, Rasmussen JT, Heegaard CW, Harrison P. Measurement of phosphatidylserine exposure during storage of platelet concentrates using the novel probe lactadherin: a comparison study with annexin V. Transfusion. 2009;49(1):99-107.

pubmed doi - Jonatan F, Chiristina Smith, and Brent L, et al. Measurement of Phosphotidylserin Exposure in leukocytes and platelet by flow cytometry with annexin V. Blood Cells, Molecules, and diseases 1999; 25:271-278.

- Hagberg IA, Lyberg T. Blood platelet activation evaluated by flow cytometry: optimised methods for clinical studies. Platelets. 2000;11(3):137-150.

pubmed doi - Wang C, Mody M, Herst R, Sher G, Freedman J. Flow cytometric analysis of platelet function in stored platelet concentrates. Transfus Sci. 1999;20(2):129-139.

pubmed doi - Hirosue A, Yamamoto K, Shiraki H, Kiyokawa H, Maeda Y, Yoshinari M. Preparation of white-cell-poor blood components using a quadruple bag system. Transfusion. 1988;28(3):261-264.

pubmed doi - Eolar G, Wihte JH. Change In Glycoprotein expression after platelet activation. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1995; 74:352-356.

- Cardigan R, Williamson LM. The quality of platelets after storage for 7 days. Transfus Med. 2003;13(4):173-187.

pubmed doi - Holme S, Sweeney JD, Sawyer S, Elfath MD. The expression of p-selectin during collection, processing, and storage of platelet concentrates: relationship to loss of in vivo viability. Transfusion. 1997;37(1):12-17.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.