| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 2, June 2015, pages 174-177

Resolution of Hypersplenism and Pancytopenia in Common Variable Immunodeficiency Patient After Partial Splenic Artery Embolization: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Safiah Hussain Sumaylia, Latifah Rashed Al Shekailia, Sulaiman Saleh Al Gazlana, Farrukh Sheikha, Hassan Al Rayesa, Hasan Hamdan Al Dhekria, Agha Muhhamad Rehan Khaliqa, Rand Khalid Arnaouta, b, c

aDepartment of Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, Saudi Arabia

bDepartment of Pediatrics, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, PO Box 3354, Riyadh 11211, MBC 46, Saudi Arabia

cCorresponding Author: Rand Khalid Arnaout, Department of Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript accepted for publication August 11, 2014

Short title: Hypersplenism and Pancytopenia in CVID

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jh168w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the second most prevalent primary immunodeficiency disorder following selective immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency but it is more complicated clinically. It causes a wide spectrum of symptoms and signs affecting several systems of the body. CVID is mostly a humoral immunodeficiency with cell-mediated immunity being affected in some patients leading to both autoimmunity and malignancy adding to the immunodeficiency, which makes the management of these patients very complicated. Gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and bone marrow are commonly affected organs by both autoimmunity and malignancy in the context of CVID. In this paper, we present a case of CVID who presented with pancytopenia secondary to hypersplenism and failed both intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and steroids treatment. She underwent partial splenic artery embolization as an alternative procedure to total splenectomy to preserve some splenic function and avoid surgical total splenectomy. Partial splenic artery embolization leads to dramatic improvement in platelets, hemoglobin and white cell count after the procedure without further compromising her immune system.

Keywords: Hyersplenism; Pancytopenia; Common variable immunodeficiency; Splenic artery embolization

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is the second most prevalent primary immunodeficiency following selective immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency [1]. It causes a wide spectrum of symptoms and signs affecting many systems of the body [1]. CVID is a humoral immunodeficiency with cell-mediated immunity being affected in some patients with increased incidence of malignancy and autoimmunity [2]. Autoimmune bone marrow and gastrointestinal tract (GIT) are commonly affected by autoimmunity, since the GIT is the largest lymphoid organ in the body [3]. In a study, 5% of CVID patients presented with nodular regenerative hyperplasia associated with portal hypertension, hypersplenism and pancytopenia [4].

Several studies documented a high prevalence of inflammatory, malignant, and infectious gastrointestinal disorders in patients with CVID or selective IgA deficiency. Interestingly, it has become increasingly apparent that antibody deficiency alone does not result in gastrointestinal disease. Rather, defects in cellular immunity predispose to celiac disease, pernicious anemia, giardiasis, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, and even inflammatory bowel disease [3].

High prevalence of autoimmunity in CVID is reported, and many mechanisms have been proposed to explain it [5]. Genetic predisposition, innate and adaptive immunity deficiency leading to persistent/recurrent infections, variable degrees of immune dysregulation, and possible failure of central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms of inductions and maintenance can contribute to increased incidence of autoimmunity [5].

Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy are common in CVID patients, although the pathogenesis of these findings is not known in all cases [6]. The longitudinal analysis of patient’s individual data demonstrated that splenomegaly was not a constant finding. In 9.8% of patients, splenomegaly is present at the time of diagnosis and during follow-up; in 16.5%, splenomegaly was firstly detected during the follow-up, but in 5.3%, splenomegaly was detectable only at the time of diagnosis and the spleen size returned to normal size during the follow-up [6]. Six patients splenectomized during follow-up because of hypersplenism [6]. In all but one, splenectomy successfully cured the cytopenia [6]. Splenomegaly is always associated with a liver enlargement (longitudinal diameter of left lobe more than 12 cm) and/or abdominal lymphadenopathy [6]. In 5.6% of patients, splenomegaly was associated with leukocytopenia (< 4,000/mm3) and thrombocytopenia (< 30,000/mm3), in 3% with thrombocytopenia only, and in 2% with leukopenia only [6].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

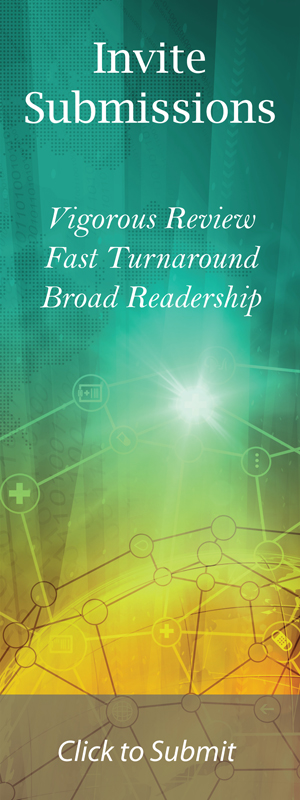

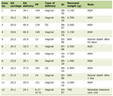

A 19-year-old girl had suffered from recurrent sinopulmonary infections since the age of 6 years and was diagnosed as a case of CVID. She was on intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) treatment and prophylactic antibiotics. She responded well to treatment with fewer infections. At the age of 11 years, she presented with intractable diarrhea which was secondary to chronic autoimmune colitis and did not respond to infliximab therapy beside her usual IVIG replacement and antibiotics. She underwent surgical bypass of the inflamed segment of the intestine. The diarrhea resolved after that. In August 2013, she presented with persistent pancytopenia along with massive splenomegaly. Hypersplenism was suspected and CT of abdomen confirmed enlarged spleen measuring approximately 20 cm, with patent portal and hepatic veins and no evidence of portal hypertension (Fig. 1). She was started on prednisone 40 mg and high dose for 3 days. She was also given granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) for leukopenia. Response to these therapies was minimal. A combined hematology and immunology evaluation was conducted and we reached the decision to proceed with splenectomy as last resort according to protocols.

Click for large image | Figure 1. CT of abdomen before embolization. |

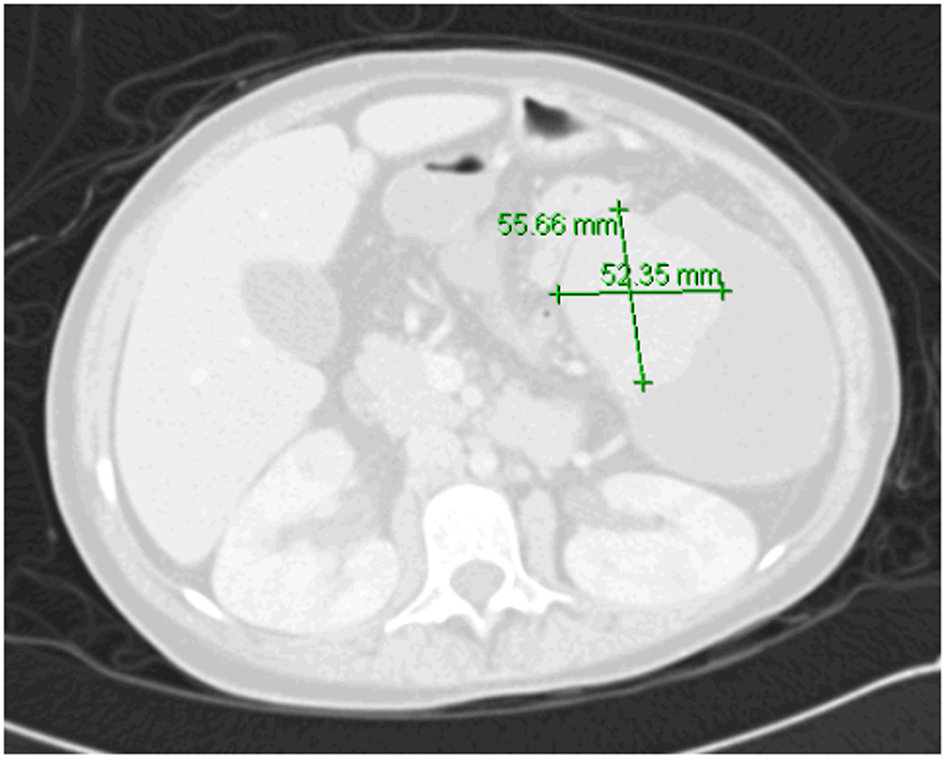

We had two concerns: one was regarding very low platelets count which could lead to pre- or post-operative bleeding, and other was that removal of spleen would further worsen her compromised immune system. To overcome these two problems, we discussed the possibility of performing partial splenic artery embolization that could help in increasing very low cell counts as well as leave behind enough splenic tissue to preserve her splenic immune function. She was given pneumococcal vaccine in preparation. Procedure was explained to patient and family who consented to it. She underwent embolization. Post-splenectomy complications included fever, leukocytosis, pleural effusion and severe pain. Then, she gradually improved and during this time, she needed morphine to control abdominal pain. When she became stable patient was discharged home. Immediately post-embolization, platelet count was above 106/dL and patient was started on aspirin. On follow-up after discharge (4 weeks after the procedure), the pancytopenia resolved. At that time, aspirin was discontinued (Table 1). There were no clinically significant infections after splenic artery embolization. Currently she has maintained normal counts 4 weeks after the procedure with Hb level of 130 g/L and platelets count of 375 × 109/L. Repeated abdominal CT scan showed the embolized spleen with remaining viable tissue and hypodensity representing necrotized tissue (Fig. 2).

Click to view | Table 1. Patient Pre- and Post-Procedure Parameters |

Click for large image | Figure 2. CT of abdomen 8 months post-embolization with remnant splenic tissue. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The traditional first-line treatment for both idiopathic thrombocytopenia (ITP) and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is glucocorticoids. In case ITP occurs while patient on IVIG replacement therapy, higher doses of IVIG can be used first (e.g. 1 - 2 g/kg) with or without steroids [7]. Recently rituximab, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, is used successfully and should be considered for patients with ITP or AIHA refractory to glucocorticoids [7-10]. In most cases, glucocorticoids are continued until the effects of rituximab can be assessed. In a retrospective analysis of 33 adults and children with ITP, AIHA, or both, overall response rate to rituximab was 85% [9]. Ten patients relapsed, of whom seven of nine responded to repeat treatment. The incidence of serious infections was not increased in patients who were receiving adequate IVIG replacement which should be continued during rituximab therapy. Thus, rituximab would be preferred over splenectomy [9].

Vinca alkaloids have also been used as a second-line therapy in steroid-resistant ITP, with moderate success [11].

Splenectomy can be used as treatment of severe refractory ITP and AIHA in patients with CVID. Earlier series reported significant rates of serious infections [8], although later studies are more encouraging. The largest series available analyzed outcomes in 45 patients with CVID from multiple centers who underwent splenectomy, 24 of whom had autoimmune cytopenias [12]. Of these, 19 had failed glucocorticoids, IVIG therapy, or both, and two had failed rituximab. Seventy-five percent experienced a clinical response to splenectomy (defined as needing no further therapy beyond low-dose maintenance glucocorticoids), while the remaining 25% either responded initially but suffered multiple relapses or did not respond and required subsequent alternative therapy. There were nine episodes of bacterial meningitis or septicemia in 40 patients (infections believed to be directly related to splenectomy), although six of these were in patients not receiving IVIG therapy. No deaths resulted from these infections. However, there were 16 other episodes of viral reactivations, fungal infections, and other serious bacterial infections, at least four of which were fatal. Overall, the mortality rate in the splenectomized patients was 1.6% per patient year, compared with an estimated rate of 2.3% in all patients with CVID and autoimmune cytopenias [12]. At 6 months follow-up, median (range) platelet counts (134.5 (71.5 - 164) × 103/μL) were significantly higher than those before treatment (33.5 (23 - 39) × 103/μL; P < 0.05). All patients developed post-embolization syndrome. Left-sided pleural effusion and increase in amount or developing new ascites occurred in six and five patients, respectively [13].

In our reported case, upon failure of medical treatment for pancytopenia we used a partial embolization of splenic artery as an alternative procedure to splenectomy using interventional radiology. We aimed to avoid bleeding in presence of very low platelets count to preserve some splenic function.

By reporting this case, we experienced partial splenic embolization as a procedure to provide clinically acceptable approach instead of total splenectomy. It might be recommended in patients with risk of surgery outweighs the benefit and at the same time, splenic immune function needs to be preserved.

| References | ▴Top |

- Vorechovsky I, Cullen M, Carrington M, Hammarstrom L, Webster AD. Fine mapping of IGAD1 in IgA deficiency and common variable immunodeficiency: identification and characterization of haplotypes shared by affected members of 101 multiple-case families. J Immunol. 2000;164(8):4408-4416.

doi pubmed - Kalha I, Sellin JH. Common variable immunodeficiency and the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6(5):377-383.

doi pubmed - Lai Ping So A, Mayer L. Gastrointestinal manifestations of primary immunodeficiency disorders. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8(1):22-32.

pubmed - Fuss IJ, Friend J, Yang Z, He JP, Hooda L, Boyer J, Xi L, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(4):748-758.

doi pubmed - Lopes-da-Silva S, Rizzo LV. Autoimmunity in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28(Suppl 1):S46-55.

doi pubmed - Quinti I, Soresina A, Spadaro G, Martino S, Donnanno S, Agostini C, Claudio P, et al. Long-term follow-up and outcome of a large cohort of patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27(3):308-316.

doi pubmed - Wang J, Cunningham-Rundles C. Treatment and outcome of autoimmune hematologic disease in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). J Autoimmun. 2005;25(1):57-62.

doi pubmed - Gobert D, Bussel JB, Cunningham-Rundles C, Galicier L, Dechartres A, Berezne A, Bonnotte B, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in common variable immunodeficiency-associated immune cytopenias: a retrospective multicentre study on 33 patients. Br J Haematol. 2011;155(4):498-508.

doi pubmed - Mahevas M, Le Page L, Salle V, Cevallos R, Smail A, Duhaut P, Ducroix JP. Efficiency of rituximab in the treatment of autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura associated with common variable immunodeficiency. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(8):645-646.

doi pubmed - El-Shanawany TM, Williams PE, Jolles S. Response of refractory immune thrombocytopenic purpura in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency to treatment with rituximab. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(6):715-716.

doi pubmed - Sikorska A, Slomkowski M, Marlanka K, Konopka L, Gorski T. The use of vinca alkaloids in adult patients with refractory chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenia. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26(6):407-411.

doi pubmed - Wong GK, Goldacker S, Winterhalter C, Grimbacher B, Chapel H, Lucas M, Alecsandru D, et al. Outcomes of splenectomy in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID): a survey of 45 patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;172(1):63-72.

doi pubmed - Abdella HM, Abd-El-Moez AT, Abu El-Maaty ME, Helmy AZ. Role of partial splenic arterial embolization for hypersplenism in patients with liver cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29(2):59-61.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.